This chapter forms the conceptual field of the most essential ideas underlying the phenotypic approach to dermatology. It develops the conceptualization of cellular—and therefore phenotypic—diversity of human skin and presents practical examples of assessing the phenotypic state of a specific skin sample. Together, these elements lead to the recognition of multiple opportunities for the fundamental transformation of dermatology, which has matured to the point of embracing a cytological understanding of its subject matter. On this basis, the core propositions of the theory of phenotypic dermatology are summarized.

“Theories must not only explain the current state of affairs; past experience must also be derivable from them.”

— Karl Popper

Initial Propositions

The following are the key ideas that define a distinct domain of dermatology—one that has matured to a cytological level of understanding and application.

On the Operational Unit in Phenotypic Dermatology

The role of theoretical assumptions is to systematize scientific knowledge by employing theoretical statements from which—guided by the rules of logic—all other statements can be derived, including those that allow empirical interpretation. The methodological function of theoretical concepts lies in their use for generalization and expansion of scientific understanding. It is well known that empirical generalizations reveal certain regularities in the functioning of phenomena and objects—regularities that, in real life, often lie beyond direct observation. Yet these generalizations do not explain the mechanism or cause of such regularities.⁴⁰

For example, a diagnosis is often established based on repeated encounters with its characteristic symptoms. However, if we understand the mechanism that gives rise to these symptoms—revealed not only through observation but at the molecular level—then we no longer need to apply laborious and often costly diagnostic procedures each time, because we already know the mechanism underlying specific rash elements. Once, even a simple magnifying lens was an expensive and not universally accessible tool. Yet the knowledge obtained through it was recorded in books as detailed descriptions of rash differentiation, enriching dermatologists’ understanding of clinical presentations and giving rise to new concepts.

In this light, an essential role of theory is to establish the connection between theoretical knowledge and empirically testable consequences. Only abstract concepts form the conceptual core of a theory and are capable of explaining empirical facts. Thus, the starting point for constructing a theory oriented toward practical application lies in the formulation of abstract concepts.

The purposeful application of cellular technologies in dermatologic practice, as discussed in the previous chapter, points to the possibility of transforming contemporary dermatology. A defining feature of this transformation is that the “unit” of investigation of skin states becomes not the visual pattern of pathological symptoms, but the characteristics of the cellular subpopulations present in a specific area of skin.

Within the field under consideration, there emerges what may be called a deficit of concepts needed to distinguish and explain a new scientific reality. This necessitates the formation of a new conceptual framework for characterizing skin states and the development of methods for generating meaning within a new type of dermatology—phenotypic dermatology.

The term phenotype—derived from ancient Greek, meaning “manifested form”—refers to the set of traits and characteristics inherent to a biological object at a particular stage of development. The phenotype of an object—in this case, a skin cell—emerges through phenogenesis on the basis of the genotype, and it changes under the influence of environmental factors. The term “phenotype” was introduced in 1909 by the Danish scientist Wilhelm Ludwig Johannsen, Professor at the Institute of Plant Physiology at the University of Copenhagen and member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences. In his work Elements of the Exact Study of Heredity, Johannsen introduced the concepts of “gene,” “genotype,” “phen,” and “phenotype” to distinguish hereditary factors from their manifestations. Earlier, in his 1903 work On Inheritance in Populations and Pure Lines, he introduced the term population (from the Latin populatio — “inhabitants”), describing a group of biological individuals of one species occupying a defined geographical area over time, partially or fully isolated from other such groups.

In cytology, a cell population refers to a group of cells homogeneous by a specific criterion. Accordingly, a subpopulation is a subset of cells distinguished from the diversity of skin cells on the basis of their functional role. The tissue or organ (in our case, the skin) represents the general or parent population for all its cells, relative to which scientific conclusions are formed.

It follows logically that each subpopulation—comprising cells that reflect a specific functional–cellular structure of an elementary skin fragment—represents its specific phenotype. Thus, the refined definition of the research domain may be articulated as follows:

Phenotypic dermatology is the branch of theoretical dermatology that studies the phenotypic diversity of human skin cells.

On Questions of the Developmental Type

The technological capabilities of flow cytometry—allowing analysis of cellular subpopulations, quantification of their abundance, and evaluation of their functional states—together with the growing demand among dermatologists for a more rigorous understanding of pathological processes at the cellular level, create the research prerequisites for developing approaches to measuring the diversity of functional states of skin cells. Along with these opportunities come a series of questions for traditional dermatologic practice—questions that the existing scientific paradigm is unable to answer.

What is the full range of phenotypic traits across all skin-cell subpopulations?

Which combinations of cellular traits determine particular functions?

What is the complete set of possible cellular functions arising from all combinations of traits across all skin-cell types?

What do specific compositions of skin-cell populations signify about the state of the skin in a given rash element and/or biopsy sample?

Which functions emerge in particular cell types when they become activated within a given skin biopsy?

Can each cell type exist simultaneously in multiple functional states, and if so, which ones?

Are there limits to the formation of cell subpopulations capable of exhibiting distinct phenotypes?

What are the properties of phenotypes formed by particular distributions of cell types and their respective functions?

What structure of cellular traits, functions, and proportional compositions should be taken as the “unit” for measuring skin states for practical use in future dermatologic research and therapy?

How can individual diagnosis of skin diseases be achieved more rapidly, if distinctions among phenotypes of cellular subpopulations remain primarily empirical?

How can newly emerging capabilities in studying skin states be used to advance dermatology, which still depends heavily on traditional diagnostic methods?

How can theoretical research on skin diseases be accelerated—outpacing clinical practice—if both the formulation of research questions and the interpretation of results rely heavily on vast arrays of empirical data and are constrained by the slow adoption of investigative technologies?

Attempts to answer such questions reveal a number of theoretical problems in contemporary traditional dermatology, namely:

There is no comprehensive understanding of the full diversity of skin-cell subpopulations, even though their states may directly influence the course of skin diseases. Reliance on empirical phenomenology is valuable, but extremely inert.

There is no established understanding of the diversity of possible phenotypes within skin-cell subpopulations. Recognizing this diversity and distinguishing all possible phenotypes could generate a wide range of new research questions that would stimulate the development of dermatology.

The relationships between specific cellular phenotypes and clinical manifestations of disease remain undefined. Such knowledge could significantly enhance the therapeutic potential of dermatology, particularly for immune-mediated skin disorders.

On the Scientific Problem and the Hypothesis of Its Resolution

As the field of inquiry expands—both in terms of questions posed and theoretical challenges encountered—objective difficulties arise in applying knowledge about the diversity of functional states of skin-cell phenotypes to diagnostic and therapeutic practice. These difficulties relate to how such diversity can be measured, how new treatment approaches can be developed, and how cellular-level phenomena can be integrated into clinical reasoning. All of this brings into focus a scientific problem that can be formulated as follows:

How is it possible to observe and understand the spectrum of skin states revealed through the study of cellular phenotypes—and to use this knowledge, both practically and theoretically, to interpret the consequences of dynamic changes in the phenotypic diversity of the skin?

This problem is philosophical in nature: we do not yet know how to think about it in order to solve it. The word problem (from ancient Greek) originally meant an obstacle or difficulty that requires practical and theoretical effort to overcome. Arthur Schopenhauer wrote: “Only through deliberately performed experiments does knowledge proceed from cause to effect—that is, along the correct path; but even these experiments are undertaken only as a result of hypotheses.”

The central hypothesis is that the identified scientific problem can be resolved if the following conditions are met:

The “unit” of diversity of skin states at the cellular level is taken to be the phenotype of skin-cell subpopulations—a specific, distinguishable set of cells forming a functional structure composed of a single cell type within an elementary fragment of skin.

A theory explaining skin states at the level of cellular phenotypes is constructed using conceptual tools that allow rigorous logical derivation of consequences from experimental results obtained at the cellular level.

The theoretical framework is developed through the synthesis of conceptual fields describing skin states in static conditions, transitions between states, and transitions induced by various artificial or natural interventions at the cellular level.

A set of conceptual constructs arising within the theory is submitted to experimental verification through diagnostic studies of skin states at the level of phenotypes of cellular subpopulations; on this basis, meaningful results may be obtained for advancing diagnostic and therapeutic practice.

New classes of problems are derived from the conceptual space of the theory, enabling the development of dermatology at a pace that outstrips the increasing complexity of skin pathology.

By critically reviewing and testing hypotheses, we eliminate those that solve the problem less effectively and retain those that solve it more efficiently and adequately. Popper writes: *“In doing so, I rely on the neo-Darwinian theory of evolution, but in a reformulated version in which ‘mutations’ are interpreted as more or less accidental errors, and ‘natural selection’ as one of the mechanisms for managing them by eliminating errors.”*⁴¹

However, there is unlikely to be a reliable logical transition from empirical facts to theoretical laws, because empirical knowledge does not contain theoretical concepts. The only path to their discovery lies in formulating broad, general hypotheses, the consequences of which can be reliably confirmed through practical observation.

Thus, in order to test the hypothesis and address the identified scientific problem, several tasks come to the forefront:

Obtain a viable heterogeneous population of skin cells and determine the subpopulation composition of these cells.

Justify an approach to constructing a conceptual field that defines the full diversity of skin-cell subpopulations for in-depth scientific investigation.

Justify the conceptual “unit” of diversity of skin states at the cellular level.

Demonstrate the utility of the constructed concepts in studying the properties of skin-cell subpopulations and in their application to diagnostic and therapeutic practice.

Solving these tasks will allow the hypothesis to be tested; once reproducibly confirmed, it will become the foundation of the theory of phenotypic diversity of skin cells.

Obtaining a Viable Heterogeneous Population of Skin Cells

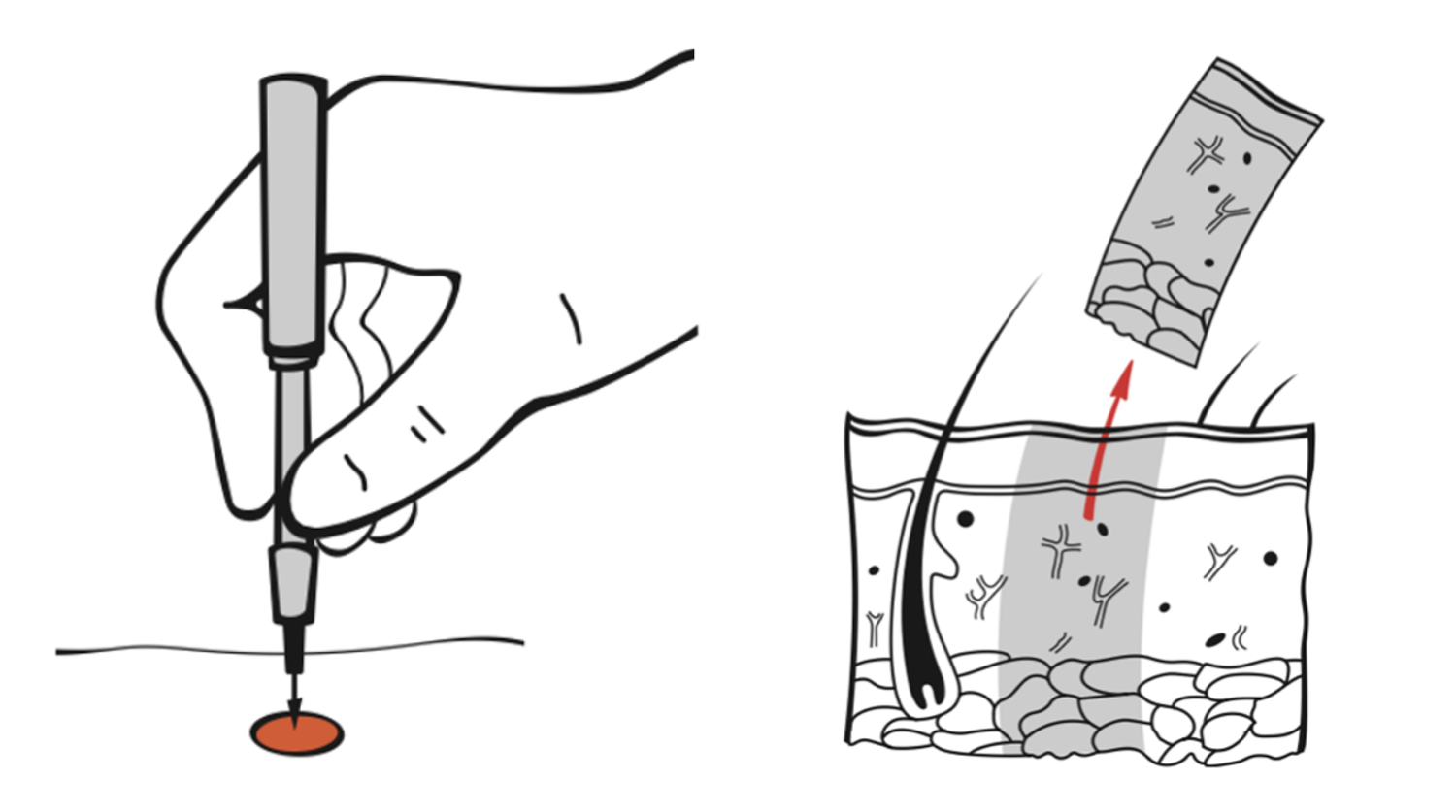

Skin biopsies for experimental research were collected using a 2-mm punch biopsy instrument (Fig. 24).

Figure 24. 2-mm punch biopsy instrument.

During sampling, the punch was positioned perpendicularly to the skin surface and advanced downward with gentle pressure while rotating clockwise and counterclockwise until the required depth was reached. The punch was then carefully withdrawn. Using a needle, the biopsy specimen was removed from the cavity and separated from the patient’s body at its lower margin with a surgical blade (Fig. 25). The resulting wound was sutured and covered with a bactericidal adhesive dressing.

Figure 25. Introduction of the punch biopsy instrument and extraction of the tissue specimen.

According to the author’s patented technique described in the invention “Method for Obtaining a Viable Heterogeneous Population of Skin Cells” (Appendix 1),⁴² the skin biopsy was immersed in 1 mL of 0.9% sodium chloride solution and placed into the processing chamber of a Medimachine automated tissue homogenization system (Becton Dickinson, USA).

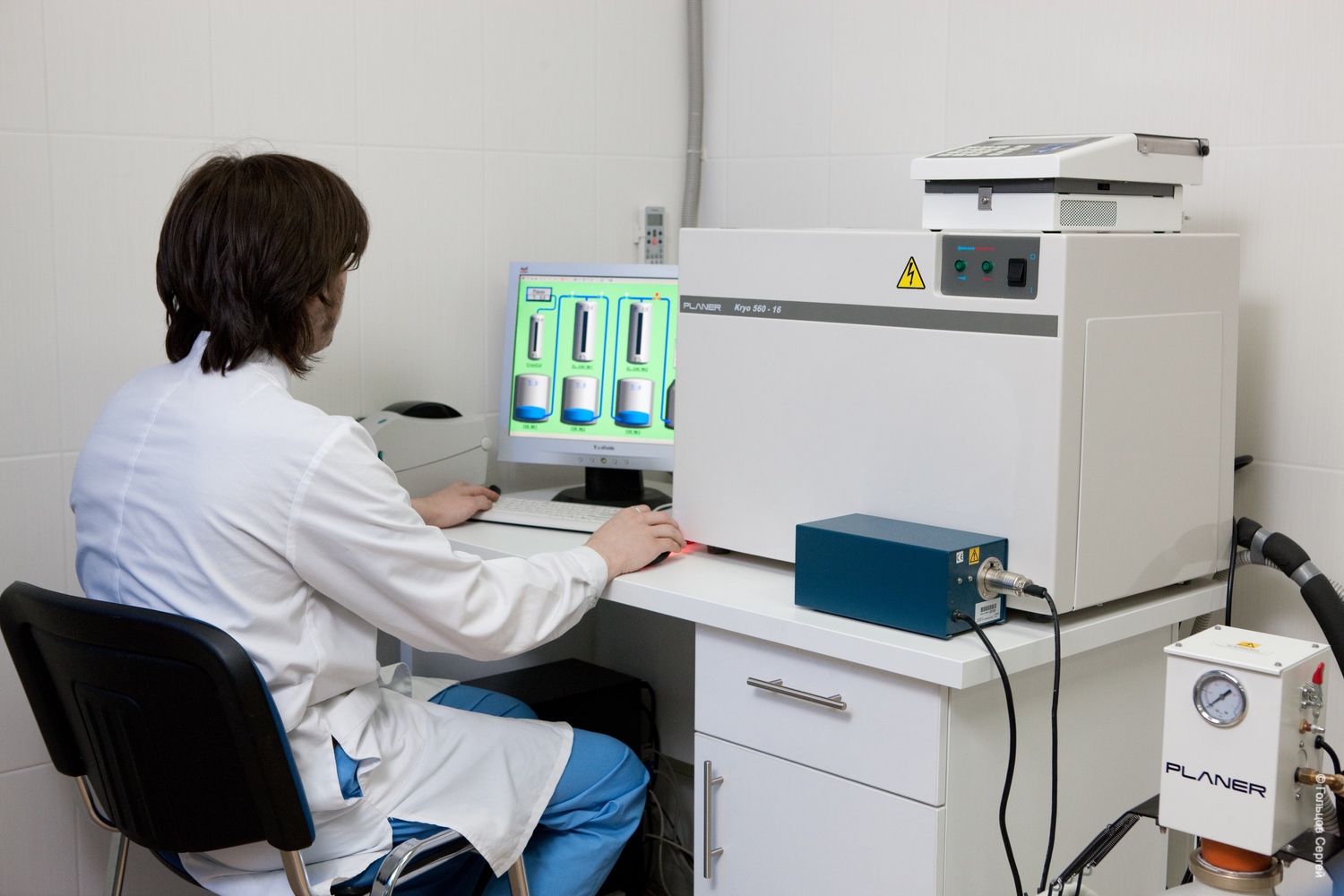

Tissue homogenization was performed for 30 seconds at +23 °C. The homogenate was withdrawn using a sterile syringe. The homogenizer chamber was rinsed three times with 1 mL of 0.9% sodium chloride solution. The homogenate was then filtered through an inert cell filter with a 20-µm nylon mesh. Afterward, the sample was centrifuged to remove the supernatant at 400 g and +23 °C for 5 minutes (Fig. 26).

Figure 26. Homogenization and sample preparation of the biopsy.

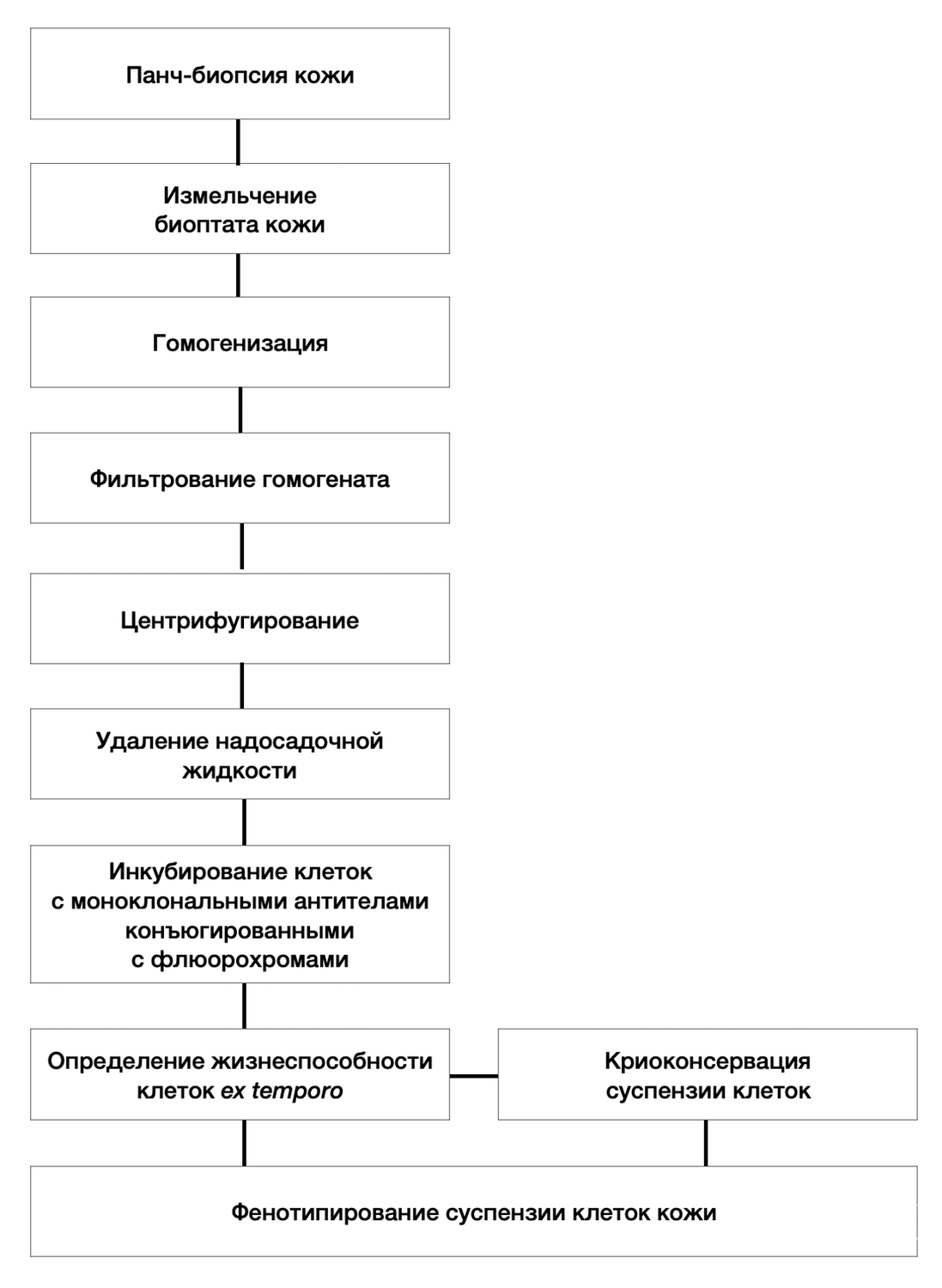

The resulting skin sample was analyzed by flow cytometry with phenotyping of the cellular suspension ex tempore and after cryopreservation. For the second variant, a sterile sample of skin cells was placed into a 2-mL Costar cryovial containing freezing medium (90% fetal bovine serum and 10% DMSO as a cryoprotectant). The sample was then frozen in liquid nitrogen vapor at –140 °C at a rate of 1 °C per minute using vitrification or a programmable tissue cryopreservation system (Fig. 27), followed by storage in a cryogenic repository (Fig. 28).

Figure 27. Programmable freezer PLANER Kryo 560-16 (Planer, UK).

Figure 28. Cryogenic storage system Taylor-Wharton K24 (IC Biomedical, USA).

Skin cells were incubated for 20 minutes in a light-protected chamber with monoclonal antibodies conjugated to fluorochromes: fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC), phycoerythrin (PE – Texas Red (ESD)), PE/Cy5 (PC5), and PE/Cy7 (PC7). Cell viability was assessed using the intracellular dye 7-aminoactinomycin D RUO (7AAD). The fundamental workflow of the method is illustrated in Figure 29.

Figure 29. Schematic workflow for preparing a viable heterogeneous population of skin cells for phenotyping in precision diagnostics.

Determining the Subpopulation Composition of Skin Cells and Obtaining the Skin Cytoimmunogram

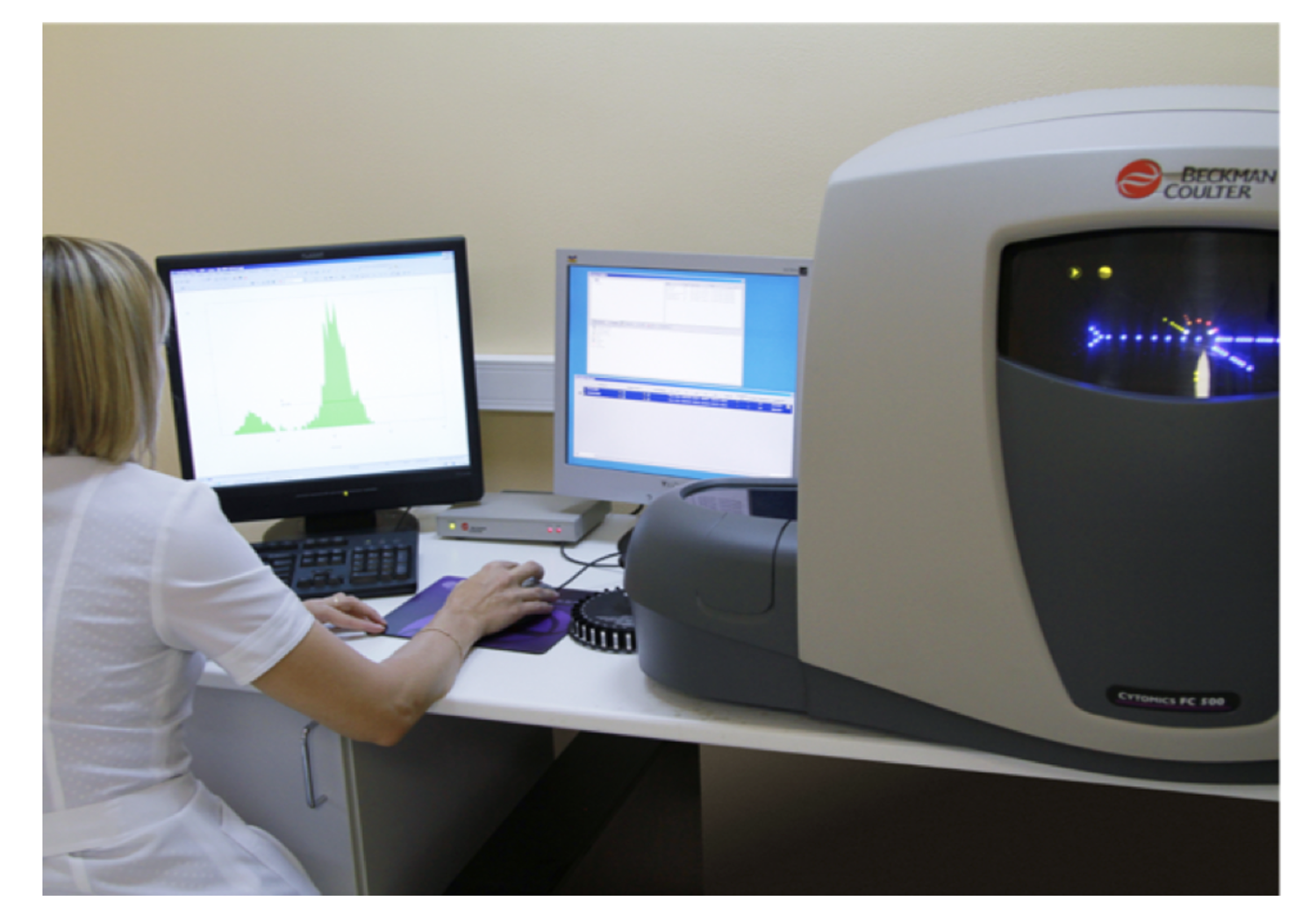

Phenotyping of the cell suspension prepared by the author’s original method, described in the invention “Method for Determining the Subpopulation Composition of Skin Cells and Obtaining the Skin Cytoimmunogram” (Appendix 2),⁴⁷ was performed on a Cytomics FC500 flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter, USA) (Fig. 30).

Figure 30. Phenotyping of the cellular suspension on the Cytomics FC500 flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter, USA).

Since resident cells are known to play the principal role in maintaining skin homeostasis,⁴³ the choice of marker sets was determined by the research objective—namely, the identification of those skin-cell subpopulations most relevant to the pathogenesis of the skin disease or condition under study. Based on established scientific data showing that keratinocytes constitute more than 90% of cells in the upper skin layer—the epidermis⁴⁴—and that the dermal cellular pool is predominantly composed of fibroblasts (fibrocytes), mast cells, monocytes (macrophages), endothelial cells, dendritic cells, and lymphocytes,⁴⁵ of which 90% are T lymphocytes located in the upper dermis and epidermis and 10% are B lymphocytes situated in the mid- and deep dermis,⁴⁶ the following markers may be used as a baseline panel to differentiate skin-cell subpopulations and characterize the dynamics of membrane events:

CD3, CD4, CD8, CD14, CD16, CD19, CD34, CD44, CD45, CD49, CD54, CD63, CD80, CD146, CD203c, CD207, CD249.⁴⁷

Taking into account their proven functional relevance, a panel of markers was defined to most precisely characterize the dynamic states of the major skin-cell subpopulations:

Keratinocytes: CD49f⁺; activated keratinocytes: CD49f⁺HLA-DR⁺

Fibroblasts: CD45⁻CD14⁻CD44⁺; activated fibroblasts: CD45⁻CD14⁻CD44⁺CD80⁺

Mast cells: CD249⁺; activated mast cells: CD249⁺CD63⁺

Monocytes: CD45⁺CD14⁺; activated monocytes: CD45⁺CD14⁺HLA-DR⁺

Intraepidermal macrophages: CD207⁺; activated forms: CD207⁺CD80⁺, CD207⁺HLA-DR⁺, CD207⁺CD80⁺HLA-DR⁺

Endothelial cells: CD146⁺; activated forms: CD146⁺CD34⁺, CD146⁺HLA-DR⁺, CD146⁺CD54⁺, CD146⁺CD54⁺HLA-DR⁺

Epithelial progenitor cells: CD34⁺CD45^dim

Lymphocyte populations:

– T lymphocytes: CD45⁺CD3⁺

– T helpers: CD45⁺CD3⁺CD4⁺CD8⁻

– T suppressors (cytotoxic T cells): CD45⁺CD3⁺CD4⁻CD8⁺

– B lymphocytes: CD45⁺CD3⁻CD19⁺

– NK lymphocytes: CD45⁺CD3⁻CD16⁺CD56⁺

Identification was performed by registering two parameters: side scatter (SSC) and fluorescence in channel FL3. To exclude from analysis any events that did not correspond in size and granularity to viable cells, appropriate logical gates were applied to histograms of forward scatter, side scatter, and CD45 expression. A minimum of 10⁶ cells was analyzed in each sample.

To document results, a medical record template titled “Skin Cytoimmunogram” (Fig. 31) was developed. This form lists the skin-cell subpopulations with their respective phenotypes, allowing laboratory personnel to record numerical results in relative and/or absolute units.

Figure 31. Medical documentation template “Skin Cytoimmunogram.”

First Significant Results

For a long time, incisional biopsy remained the only method capable of providing objective information about the morphofunctional state of skin cells. Its invasiveness, however, limited its application and virtually excluded the possibility of dynamic observation. Owing to the unique structural connections between skin cells, which prevent their separation and study in a viable in vitro state, this task proved difficult—but ultimately solvable. The invention “Method for Obtaining a Viable Heterogeneous Population of Human Skin Cells” (Appendix 1) and the invention “Method for Determining the Subpopulation Composition of Skin Cells and Producing the Skin Cytoimmunogram” (Appendix 2) opened new research opportunities for both the theoretical and practical advancement of traditional dermatology.

The idea of studying the comparatively static state of the inflammatory infiltrate—which, unlike circulating blood cells, does not change rapidly—provides an objective representation of ongoing processes in the skin and enriches information about a given skin disease through the use of targeted marker panels. In addition to greatly increasing diagnostic precision, this approach aligns with the principles of targeted therapy, which relies on information about molecules of the internal environment for the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of disease.⁴⁸ Therapy becomes oriented toward specific molecular targets within the patient’s cells. These inventions were presented to the scientific community at the 10th International Conference of Immunologists of the Urals (Fig. 32).

Figure 32. Presentation “On the Prospects of Using the Skin Cytoimmunogram” at the 10th International Conference of Immunologists of the Urals (Tyumen, 2012).

According to the conference resolution, the inventions were recognized as promising for the development of dermatology and practical for the treatment of skin diseases. The patents presented were recommended for implementation in the public healthcare system (Fig. 33).

Figure 33. Presidium of the 10th International Conference of Immunologists of the Urals with International Participation (Tyumen, 2012).

Left to right:

E. A. Kashuba, Rector of Tyumen State Medical Academy, Professor, MD, PhD; N. S. Brynza, First Deputy Director of the Department of Health of the Tyumen Region, Head of the Department of Healthcare Organization and Public Health, Tyumen State Medical Academy, Professor, MD, PhD; V. A. Chereshnev, Academician of the Russian Academy of Sciences and the Russian Academy of Medical Sciences, President of the Russian Scientific Society of Immunologists and the Ural Society of Immunologists, Allergologists, and Immune-Rehabilitation Specialists, Director of the Institute of Immunology and Physiology of the Ural Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Chair of the State Duma Committee on Science and High Technologies, Professor, MD, PhD; V. P. Melnikov, Academician of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Director of the Tyumen Scientific Center of the Siberian Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Professor, Doctor of Geological Sciences; I. A. Tuzankina, Academic Secretary of the Institute of Immunology and Physiology of the Ural Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Professor, MD, PhD; A. A. Yarylin, Professor, MD, PhD.

Together with reproducible confirmation of the initial hypothesis, these inventions serve as the empirical foundation of the theory of phenotypic diversity of skin cells, thereby opening a new space for continued theoretical and practical research.

Phenotypic Diversity of Skin Cells

The implementation of the ideas outlined above relies on mastering the full diversity of possible states of skin cells and understanding the dynamics of these states under various conditions. Knowledge of this diversity can be obtained through theoretical generalization of experimentally observed phenomena—specifically, the states of subpopulations of all types of cells within elementary fragments of skin that possess distinct functional structures. The possibility of such generalization is provided by the methods of conceptual analysis and synthesis, which serve as tools for clarifying the meaning of complex subject domains.⁴⁹

This generalization is further carried out in the form of a conceptualization of the phenomenology of skin states, enabling the derivation of logically rigorous conclusions from the results of experimental studies of the skin at the cellular level. On this basis, a conceptual field can be developed to define:

states of the skin in static conditions,

natural transitions between these states, and

transitions induced by various forms of artificial intervention at the cellular level.

Specific Features of the Approach

The essence of conceptualization lies in the justified formulation of concepts that bring clarity to an otherwise diffuse subject domain, thereby enabling the derivation of logically rigorous conclusions. The most productive method of conceptualization involves the use of conceptual technology, developed within the applied scientific field “Conceptual Analysis and Design of Organizational Management Systems” (the S. Nikanorov school).⁵⁰

These methods are used to construct and synthesize concepts in areas of practice that require conceptually strict distinctions within their reality. Their application makes it possible to theoretically advance the results of the experimental investigation of human skin presented above.

A key feature of this technology is that the construction of concepts and conceptual systems proceeds only after substantiating certain semantic representations of the essential attributes of the subject domain—representations that serve as the nuclei of formal axiomatic theories. This, in turn, enables the use of mathematical apparatus. Conceptual technologies employ the mathematics of structures (genres) of N. Bourbaki.⁵¹

This creates the possibility of building generalized theories of the subject domain from foundational representations and, through formal methods, deriving logically consistent consequences in the form of a wide variety of new (specific) concepts.

The advantage of conceptual technology for explaining the dermatological phenomena uncovered in this research lies in its instrumental logic: thinking begins with observable and systematically interpreted concrete examples of skin; from there it ascends to their abstract representations; and from those representations it further ascends to the full diversity of concrete manifestations—namely, the ensemble of specific concepts across the subject domain.

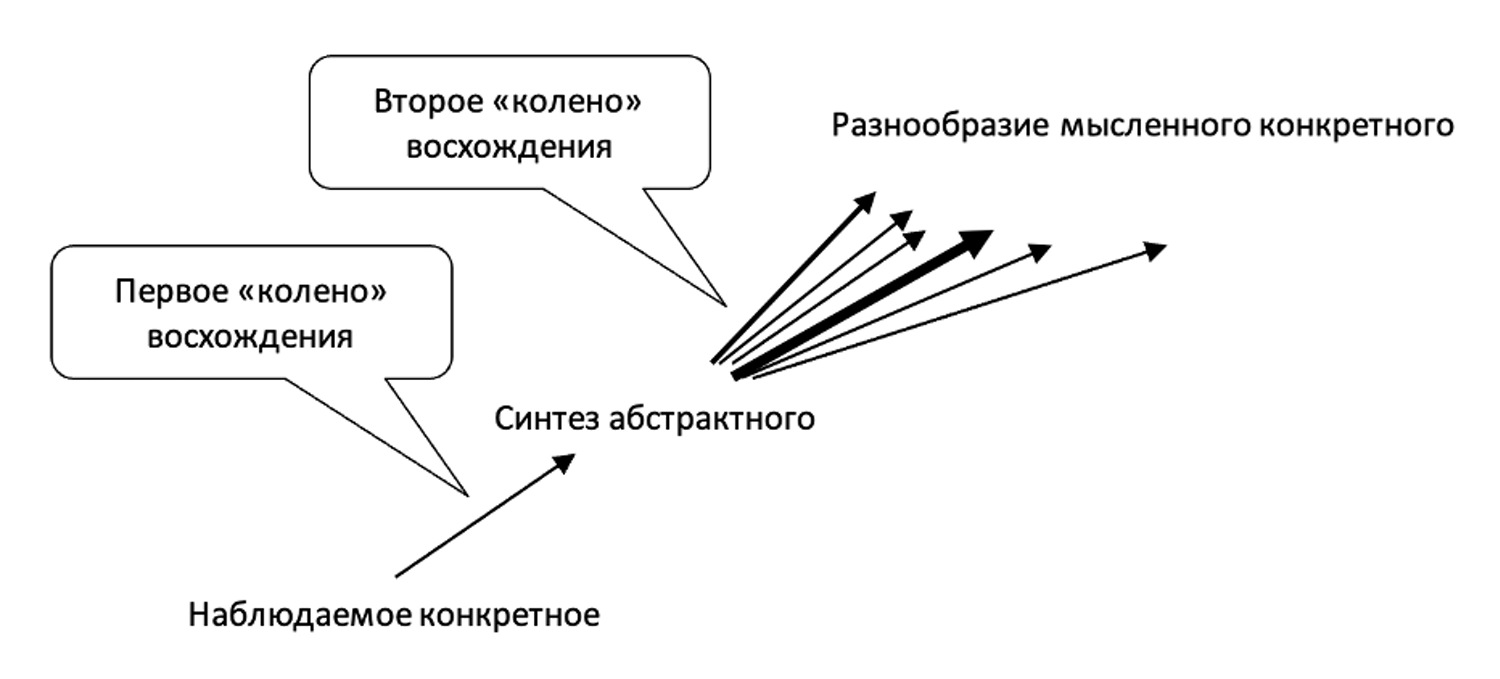

This logic is based on the method known as the “two-step ascent” (Fig. 34), which in the works of S. P. Nikanorov has been shaped into a technological procedure that enables a structured transition toward new knowledge of the concrete.⁵²

Figure 34. The “two-step ascent” method.

In conceptual technology, the form of ascent from the abstract to the concrete takes the form of operations involving the synthesis of structural genera. These operations allow us to significantly expand our understanding of the diversity of effects revealed at the cellular level of skin investigation.

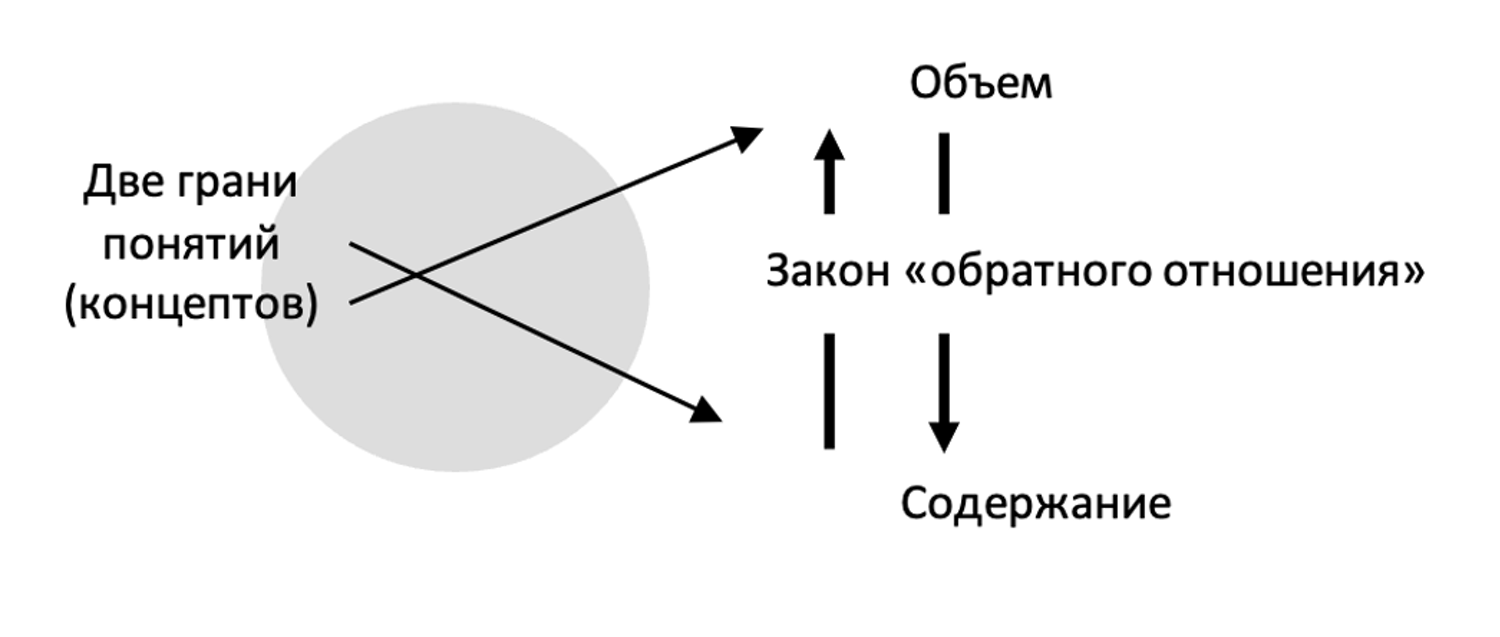

Another useful feature of conceptual technology in the present context is that the generic structures of a subject domain are constructed as a system of concepts, representing entities at different depths of abstraction. This means that when defining any component of the subject domain, the researcher consciously fixes the level of abstraction at which the cognitive work will take place. As a result, operations involving concepts manipulate a limited and well-defined set of objects that fall under these definitions. This reflects the law of the inverse relationship between the content and the scope of concepts (Fig. 35). In other words, operating with concepts is equivalent to operating with the sets of objects that fall within their scope.

Figure 35. Law of the inverse relationship between a concept’s content and its scope.

Because any concept can be used to form meaningful relationships with other concepts, this enables the generation and transformation of constructs with fixed sets of objects—that is, to generate new varieties and operate with them. A consequence of this capability is that, when the content of the relationships in the conceptual system is explicitly defined, one can perform operations on the sets (scopes) of concepts, and from the results of these operations reconstruct their content.⁵³

In generalized form, the logic of conceptualization can be represented through the following operations:

Interpretation of the subject domain, formed through the experimental investigation of dermatological phenomena at the cytological level. The essence of interpretation lies in formulating judgments about its key components and their relationships—in other words, forming the initial representation of the domain. This step should yield generalizations sufficient for constructing its generic conceptual scheme.

Construction of the generic conceptual scheme as a formal axiomatic theory. This abstract scheme defines the full diversity of all possible states of cellular diversity of the skin permitted by its axioms—including the states underlying axiomatization (i.e., results from flow-cytometric analysis of viable heterogeneous skin-cell populations) as well as all other logically possible states.

Derivation of specific concepts (terms) that are logically permissible within the constructed generic scheme. These concepts may represent skin states that have not yet been experimentally observed but are theoretically possible. At this stage, the scale of the diversity of potential skin-state phenomena—those that may later be revealed experimentally—can be estimated.

It appears that the use of conceptual analysis and conceptual “clearing” of the subject domain will make it possible to theoretically extend current research results on the human skin.

Next, the conceptualization of the phenomenology of skin states in the static mode is carried out. These states may be regarded as instantaneous “snapshots” of the dynamic evolution of skin conditions.

Baseline Characterization of the Phenomenology of Skin States in the Static Mode

Within this subject domain, it becomes possible to formulate concepts that define the full diversity of cellular subpopulations, distinguishing among all conceivable cellular traits, activity states, and functions within the structure of a specific skin biopsy.

The essence of the initial distinctions may be presented in the following assertions:

A limited number of cell types participate in the formation of skin-state phenomena. It is generally accepted that there are twelve such types (K = 12), five of which belong to the lymphocyte lineage.

Each cell type possesses a specific set of traits that can be detected using markers—clusters of differentiation (CD) molecules on the cell surface.

Each marker functions as an unambiguous indicator of a particular cellular trait. The number of known CD markers continues to grow as science advances, and their indicative roles become increasingly refined. It is assumed that more than 400 exist. However, each experimental act uses only a limited subset of these markers.

Every combination of cellular traits corresponds to the activation of a specific function.

Thus, the full range of potentially possible functions for any given cell is determined by the combinations of all its traits.

For each cell type, only a limited number of traits (24) is used in the present analysis.

This inevitably affects the precision with which we can recognize the diversity of cellular traits and, consequently, cellular functions. If we let X₁ denote the set of experimentally detectable cellular traits (CD markers) for any cell type, then the full diversity of that cell’s traits corresponds to B(X₁)—the Boolean power set (the set of all subsets of X₁).

And since each combination of traits corresponds to a specific function, this Boolean structure simultaneously represents the entire space of functions that any cell may exhibit, regardless of its type.

For example, if the number of detectable traits per cell is P, the number of possible trait combinations—and therefore potential functions—is 2ᴾ.

Given that P = 24, the maximum theoretical diversity of cellular functions (F) exceeds 16 million (specifically: F = 16,777,216).

Each of these functions may, in principle, be distinguishable. This reasoning allows the theoretical derivation of every potential cellular function, formulation of tasks concerning methods for detecting these functions, and development of methods for activating or suppressing them.

In current dermatologic practice, only an insignificant portion of the total functional diversity of skin cells is taken into account. Some functions may never manifest, or may do so only in rare or unique circumstances. Yet lacking justified claims to the contrary, we cannot exclude the emergence of previously unknown cellular functional phenomena.

Living cells are always active, but their activity manifests differently and influences skin states in different ways.

Cellular activity is the expression of a specific function within the structure of a given punch biopsy. If a cell exhibits no detectable functional traits—i.e., the empty subset (∅)—it is considered functionally passive, even though it is alive.

Cells organize into subpopulations.

Each subpopulation contains a specific set of cells of different types, each exhibiting various functions. All theoretically conceivable compositions of such subpopulations are permissible, since no constraints on their diversity are known.

A subpopulation with a specific composition of cells—each possessing a specific function—constitutes its phenotype.

Each phenotype of a cellular subpopulation uniquely corresponds to a specific immunological state of the skin, which manifests as a clinical or physical symptom.

These propositions serve as the foundation for creating a conceptual scheme that reflects the full, theoretically possible diversity of skin-state phenomena and enables the theoretical differentiation of the multitude of situations that may arise in the skin at the cellular level.

Conceptual Scheme of Skin States in the Static Mode

This scheme⁵⁴ is built upon two foundational concepts, expressed as sets, which together define the diversity of skin states:

X₁ — the set of skin-cell types; that is, all unique cell types participating in the formation of the phenomena associated with skin health.

X₂ — the set of distinctive cellular traits experimentally detected using specific markers.

The generic relationship between these concepts is determined by the fact that each cell type can exhibit all possible groups of traits, and any number of cells of each type may appear in a given subpopulation. In the language of the theory of structural genera, this relationship has the following form:

D ∈ B(Х1 × В(Х1)),

where “×” denotes the Cartesian product of sets, and “B” denotes the Boolean power set (the set of all subsets of the original set).

The type of this structure is: “A set of subsets of pairs: a cell type and the group of traits belonging to it.”

This structure defines the full diversity of situations that may arise within subpopulations formed by specific compositions of skin cells with specific traits—and therefore with specific functions. It expresses all situations in which, within a particular punch biopsy, one may consider separately those subpopulations composed of cells of all types, or only some types, together with their manifested functions. Their diversity is vast, yet measurable. For example, with 12 cell types and 24 traits, the number of possible subpopulation phenotypes reaches 2201326592.

In essence, this generic conceptual scheme defines the entire theoretically possible phenotypic diversity of the skin, unrestricted by the cardinalities of the sets composing the generic structure. It makes it possible to distinguish phenotypes with complete or incomplete sets of cell types, across all combinations of functional activities—including those in which all cell types simultaneously exhibit all their potential functions.

Theoretically, such distinctions arise as specific concepts (terms) that are logically derivable from the conceptual scheme D by formal means. For example, phenotypes of subpopulations composed of cells that are passive in a particular punch biopsy (i.e., cells expressing no functions) are formally derived from the generic conceptual scheme as the term T₁:

Т1 = {х ∈ Х1 | (∃d ∈ D) & (pr1 d = x) & (pr2 d = Ø)}.

Within the generic conceptual scheme, unusual yet theoretically possible situations become distinguishable.

For example, the case in which cells of the same type exhibit different sets of functions (term T₂). Such scenarios compel researchers to address questions about the properties of these phenotypes and how they relate to immunopathogenesis—central objects of study in dermatology as a science of the skin and its diseases.

Т2 = {t ∈ B(Х1) | (x1 ∈ t) & (x2 ∈ t) & (x1 = x2) ⇒ ((∃d1 ∈ D) & (∃d2 ∈ D) & (pr1 d1 = x1) & (pr1 d2 = x2) & (pr2 d2 ⋂ pr2 d1 = Ø))}.

Examples of possible phenotypically distinct skin states include the following situations.

Term T₃:

Т3 = {t ∈ B(Х1) | (∃x2 ∈ X2) & (∀x1∈t ∃d ∈ D) & (x1 = pr1 d) & (x2 ∈ pr2 d)}.

Term T₄:

Т4 = {t ∈ B(Х1) | (x1 ∈ t) & (x2 ∈ t) ⇒ ((∃d1 ∈ D) & (∃d2 ∈ D) & (pr1 d1 = x1) & (pr1 d2 = x2) & (pr2 d1 = pr2 d2))}.

Term T₅:

Т5 = {t ∈ B(Х1) | (x1 ∈ t) & (x2 ∈ t) & (x1 ≠ x2) ⇒ ((∃d1 ∈ D) & (∃d2 ∈ D) & (pr1 d1 = x1) & (pr1 d2 x2) & (pr2 d2 ⋂ pr2 d1 = Ø))}.

Term T₆:

Т6 = {t ∈ B(Х1) | ((∃d ∈ D) & (pr1 d = pr2 t) & ((x1 ∈ pr1 t) ⇒ ((∃1d ∈ D) & (pr1d1 = x1) & (x2 ∈ pr2 d1) ⇒ (x2 ∈ pr2 d))))}.

This allows the investigation of whether the simultaneous manifestation of the same function by different cell types alters its overall influence on the skin.

Term T₇:

Т7 = {t ∈ Х2 × B(X1) | (x1 ∈ pr2 t) ⇔ ((∃d ∈ D) & (x ∈ pr1d) (pr1 t = pr2 d) & (pr2 t = pr1 d2))}.

Through such derivations, all theoretically possible combinations of cellular compositions across all types of subpopulations—with their corresponding functional characteristics—can be obtained. This enables the identification of classes of potential situations that remain indistinguishable within current dermatology. This explains why the vast diversity of skin diseases encountered by practicing dermatologists has yet to acquire specific names or individualized therapeutic approaches.

Naturally, this opens the possibility of creating a theoretical foundation for multiple classes of experimental studies on the properties of the phenotypic diversity of the skin and, on this basis, formulating new classes of research problems concerning states of health and disease across different functional compositions and specific sets of cell types.

On Expanding the Subject Domain of Phenotypic Diversity of Skin-Cell States

The conceptualization presented above yields a static representation of the diversity of possible states of skin cells. This result is useful for a certain class of theoretical—and therefore practical—tasks in dermatology. However, it is evident that this representation cannot encompass the full range of problems in the field. To address this limitation, further work is planned in the direction of conceptualizing additional subject domains. At present, at least two such directions are envisioned.

Elaboration of theoretical representations of the possible phenomena of transitions between skin states and the mechanisms underlying them.

This concerns the development of a theoretical framework for the dynamic diversity of skin states. Within this domain, all types of changes in skin-cell states can be distinguished. In doing so, it will be necessary to consider, for example, the fact that cells of each type may exhibit (or fail to exhibit) several distinct functions, altering their properties (i.e., combinations of traits) over time.

Elaboration of representations of the phenomena and mechanisms of induced transitions of skin states.

This subject domain encompasses the events arising from various forms of artificial or natural intervention that influence the states of skin cells.

These directions constitute the future trajectory of both theoretical and experimental development of phenotypic dermatology. Nevertheless, the established picture of skin phenomena at the cytological level already allows the formulation of initial conclusions regarding the directions of its practical application.

First Consequences of the Phenotypic Approach to Dermatology

The initial consequences of the established approach may be summarized as follows:

All inflammatory processes in the skin—and the pathogenetic cellular mechanisms underlying them—must be viewed as parts of a single whole.

Through their interactions, these components determine the full diversity of observable rash elements and their transformations. Thus, in any investigation of the skin, it must be recognized that we are dealing with a system of heterogeneous objects unified into a coherent entity. Moreover, each part of this system (in our case, a cellular subpopulation) and even each individual cell may be regarded as an integrated whole composed of its own components and, accordingly, can be studied as a system in itself.

The absence of an obvious connection between empirical and theoretical concepts does not preclude the establishment of either logical relationships or distinctions between them.

Developing this idea further, it should be noted that observations alone—without theoretical interpretation—cannot serve as the foundation for conclusions, nor for confirmation or refutation of a hypothesis or theory. Without theoretical explanation, observed facts may remain accidental and poorly understood data; they certainly cannot serve as meaningful sources of information capable of clarifying the clinical picture observed by the dermatologist.

The methodological capabilities gained from the new approach to studying skin-cell subpopulations open the doorway to the next section of this work.

The Theory of Phenotypic Diversity of Skin Cells

The conceptualization of the phenomenology of states and dynamics of skin-cell subpopulations has brought previously hidden circumstances to an explicit level. These capabilities impart an expansive character to the emergence of research tasks that could not have been formulated earlier. Each type of such task corresponds to the challenge of recognizing specific properties within the complex morphology of skin cells:

tasks aimed at identifying the full diversity of skin cells of each type, including all possible traits and functions of cells of each type;

tasks of diagnosis—identifying the effects of potential functions and their combinations on skin states;

tasks aimed at discovering ways to activate or suppress the functions of cells of each type;

tasks focused on identifying the properties of transitions between states of cell populations with diverse functional capabilities;

tasks identifying the concentrations of specific cell types with variously activated functions in particular states of the skin;

tasks aimed at discovering methods for intentionally altering (regulating) the transitions between states of cell populations, and others.

The derivation of these tasks has become the basis for formulating new, more refined experiments, and simultaneously serves as a generator of requirements for expanding the experimental capabilities of dermatology—capabilities that depend on distinguishing among phenotypes of skin-cell subpopulations.

Further refinement of conceptual distinctions among states of skin-cell subpopulations and their dynamics has revealed classes of potential situations that remain indistinguishable in dermatology today. It is no coincidence that the aim of this work is to resolve the mismatch between new facts and old methods of explaining them through the construction of a theory—one that explains skin states at the level of phenotypes of its cellular subpopulations and is suitable for the practical and theoretical development of dermatology, as well as for the pragmatic use of knowledge about the consequences of dynamic changes in the phenotypic diversity of human skin cells.

According to Linus’s Law, *“Theory and practice sometimes collide, and when that happens, theory loses—always.”*⁵⁵

And yet, the most pragmatic and transformative step toward practice is the creation of a theory in which principles and generalizations express the objective, real relationships among the elements of a system. Newton called this the method of principles, but today it is known as the hypothetico-deductive method, because it uses principles or hypotheses as axioms—principles that reflect essential properties and relationships of the phenomena and processes under study. Standards for producing theoretical knowledge grant it far greater plausibility and reliability than empirical knowledge, though they do not transform theory into absolute scientific truth. Theory does not eliminate the risk of error; errors may be revealed when theory is compared to real-world evidence. Like all forms of scientific knowledge, theory is only relatively true—and it is no exception.

However, because of the deductive logical relationships between propositions and laws, the conclusions of a theory possess greater plausibility than its individual elements—or even than the sum of those elements.

First, when theory is understood as a form of rational, systematic activity, it is sharply distinguished from practical activity, including such specific forms of scientific practice as observation and experimentation. Second, in characterizing theory as a rational form of cognition, it is thereby contrasted with empirical knowledge, which is directly connected to sensory-practical activity. Yet this contrast is relative, arising within the broader distinction between rational and sensory cognition. Third, it is the systematic character of all knowledge included within a theory that gives it the necessary coherence and unity. When considered through the lens of the categories of the abstract and the concrete, a complete theory can be viewed as concrete knowledge, while its individual components function as abstractions.⁵⁶

With this preliminary characterization of theory in place, we may logically define it as a conceptual system whose elements are concepts and judgments of varying levels of generality—generalizations, hypotheses, laws, and principles. All are connected by two forms of logical relations.

The first type consists of logical definitions, through which all secondary concepts are determined using the primary, foundational concepts of the theory.

The second type consists of deductive relations, through which theorems, derivative laws, and other statements are logically derived from the axioms, fundamental laws, or principles of the theory.

First, it must be noted that theories are classified by the depth with which they reveal the specific properties and regularities of the processes under investigation. Since our scientific inquiry began with observing properties arising from the unique and diverse relationships among skin cells—that is, with observable phenomena—the theory should be classified as phenomenological.

The primary and secondary morphological elements of rash familiar to dermatologists are concepts describing observable phenomena and therefore carry an inherent degree of subjectivity in interpretation. Yet we have taken a step toward uncovering the mechanisms governing these phenomena, and thus toward their deeper and more complete explanation. Theoretical concepts are used to describe unobservable objects and phenomena—such as the molecules on the surface of cells that express cellular functions and are detected using flow cytometry.

By proposing a hypothesis concerning the unobserved cells of the skin and their functions, and applying conceptual abstractions, we attempted to demonstrate the connection to an already observable object—the elementary fragment of skin or the infiltrate of a morphological element. Accordingly, the theory can be characterized as phenomenological-explanatory.

In turn, this opens the possibility of formulating the propositions of the theory of phenotypic diversity of human skin cells, propositions that bring into logical relationship the previously isolated facts about the role of skin-cell phenotypes revealed in this research.

Propositions of the Theory

The “unit” that explains the diversity of skin states at the cellular level must be understood as the phenotype of a cellular subpopulation.

This unit represents a subpopulation composed of skin cells of a single type that possesses a distinctive (specific) functional–molecular structure. It enables the differentiation of subpopulations with the full range of functional activities—including those in which every cell type simultaneously expresses all of its functions.

Skin cells exist within the context of the functions they perform and through their intercellular relationships.

The overall state of the skin derives from the foundational understanding that its cells are interconnected. The skin is a dynamic system of interrelated objects and events. The phenotype of a subpopulation is observable and is conditioned by the biopsy from which it is obtained.

No property of any fragment of skin is fundamental on its own. All properties of one cell arise from the properties of other cells. The interconnectedness of these relationships defines the structure of a phenotype and provides complete information about the state of the skin fragment within the biopsy—though not necessarily the entire skin.

The method for obtaining a heterogeneous population of skin cells makes it possible to separate cells while preserving their viability.

This enables subsequent diagnostic studies, as well as the isolation and culture of individual subpopulations.

The technical result—which includes biopsy acquisition, tissue homogenization, homogenate filtration, centrifugation, viability assessment, incubation with fluorochrome-conjugated monoclonal antibodies, and phenotyping with quantification of cells expressing specific phenotypes—constitutes both a method for determining the subpopulation composition of skin cells and a method for generating the skin cytoimmunogram.

Determining the subpopulation composition of skin cells enables quantitative and functional assessment of the states of viable skin-cell subpopulations in different sex and age groups.

This allows for establishing correlations between structural and functional parameters of the examined cells, and can be applied in screening programs.

The results of conceptualizing the phenomenology of skin states at the cellular level may significantly increase the precision of skin diagnostics.

Diagnostic assessment can be based not on the morphological appearance of pathological symptoms—determined visually—but on the measurable properties of distinguishable subpopulations of cells within the specific region of interest.

Evaluating the subpopulation composition of cells already enables the study of skin diseases characterized by substantial changes in cell counts and the emergence of unique membrane events.

Together, these changes characterize specific clinical states.

An effective tool for the development of theoretical knowledge about skin states—knowledge obtained through experimental work—is one grounded in the synergy between dermatology, immunology, and the methods of conceptual analysis and synthesis of complex subject domains.

This synergy makes it possible to formulate and explicitly represent concepts describing the full diversity of skin states distinguishable at the cellular level.

A rational approach to constructing concepts of phenotypes of skin-cell subpopulations lies in the systematic explication of experimental results through the development of generic conceptual schemes.

These include:

the phenomenology of skin states in static conditions,

the phenomenology of transitions between states (dynamics),

the phenomenology of transitions induced by various types of interventions.

Synthesizing these conceptual schemes will make it possible to generate many concepts that differentiate and reveal the properties of the entire diversity of components constituting the real picture of skin states.

The advancing directions of dermatology—those using phenotypes of cellular subpopulations as the “units” of skin-state investigation—must arise not from flashes of insight by talented researchers, but from formulating tasks aimed at identifying the properties of systematically derived specific concepts of formal theories.

These theories are constructed from generic conceptual schemes.

Such a mode of working with the unknown in dermatology will generate a field of forward-looking research that stays years ahead of the natural evolution of skin pathology.

Concepts of phenotypes of skin-cell subpopulations and other phenomena related to skin states must be used as formal tasks for planning experiments, developing diagnostic and therapeutic devices and preparations, and posing new classes of research questions.

Deepening the conceptual distinctions of states and dynamics of skin-cell subpopulations—through the expansion of generic structures of these dynamics and the interpretation of formally defined terms—will allow hidden aspects of skin pathology to be brought to the explicit level and will support the development of new therapies.

On the basis of distinguishing the properties of specific subpopulation phenotypes, new classes of research problems addressing “health / pathology” situations can be formulated.

The cognitive capabilities associated with studying phenotypes of skin-cell subpopulations, together with the specific rules for conducting such studies, form a new field of medicine—phenotypic dermatology.

Its foundation must consist of knowledge concerning the properties of all possible phenotypes of skin-cell subpopulations.

The shift from a symptomatic approach in skin research and therapy to a phenotypic approach represents the transition to a new type of dermatology—phenotypic dermatology.

It offers a model of deep penetration into the nature of skin diseases and opportunities approaching those of digital technologies.

Within this paradigm, skin states can be computed.

This is essential for enabling dermatology to achieve a prognostic capability regarding the progression of skin pathologies—one that significantly outpaces their natural evolution—and for strengthening the intellectual power of diagnosis and therapy.

Integrity and Balance of the Theory

The axiomatic method, first used by the ancient Greek mathematician Euclid, postulates that all statements contained within a theory must be logically derived from a small number of initial assumptions taken without proof. It is evident that such an ideal can never be fully achieved in theories based on observation, experimentation, and empirical fact. New observations, accumulated experience, and the synthesis of scientific knowledge compel us to revise existing assumptions and principles. Yet the pursuit of this ideal encourages the search for logical connections between judgments that are disparate in nature, thereby achieving a holistic representation of the object of study.

The integrity of a theory is evaluated through the following key aspects:

The foundational principles (basic postulates of the theory) must be justified and demonstrated, or accepted within the scientific community as reasonable and productive.

This aspect is represented in dermatology by the diagnostic algorithm, which is essentially an empirical foundation: a body of knowledge accumulated by dermatologists through direct interaction with the objects and phenomena of the subject domain—the diverse states of human skin.

All tasks, questions, and contradictions arise from the professional need to know about skin states quantum satis (“as much as is needed”) to make an accurate diagnosis and prescribe effective treatment.

Phenotypic dermatology refines this aspect by describing the functions of skin cells in health and disease through the skin cytoimmunogram and by expressing these functions within conceptual schemas.

Logical consistency: the theory must not contain internal contradictions; its propositions must be mutually coherent.

Concepts and formal calculi must be well defined and internally compatible.

Systemicity: the theory must constitute a coherent system of interconnected concepts, laws, and principles, not merely a set of isolated statements.

Completeness: the theory must cover all essential aspects of the object or phenomenon under investigation, leaving no significant gaps.

Consistency with empirical data: the theory must be supported by factual and experimental evidence and must predict new phenomena.

Capacity for development: a coherent theory must allow refinement and expansion without undermining its foundational structure.

This includes the theory’s inferential operations, procedures, and evaluative criteria.

Phenotypic dermatology—describing the functions of skin cells in health and pathology, grounded in the method of the skin cytoimmunogram and expressed through conceptual schemas—seeks objective facts that are amenable to verification and cross-checking. Only such a theory may confidently answer the questions “what?”, “why?”, and “how?”. By resolving these, dermatologists become maximally effective in both prognosis and the practical orientation of their judgments, treatments, and scientific inquiries.

Most importantly, phenotypic dermatology becomes the language through which dermatologists communicate with researchers and with future generations of dermatologists.

The demonstrated methods of studying skin-cell subpopulations have revealed a landscape for which contemporary dermatology still lacks a clear understanding of the mechanisms underlying the observed results. Meeting the criteria described above renders the theory both integral and balanced—but the striking demonstrability of these phenomena suggests that a new chapter is beginning in this scientific discipline.

40 Рузавин, Г. И. Методология научного познания: Учебное пособие для вузов / Г. И. Рузавин. – М.: ЮНИТИ-ДАНА, 2012. – 287 с.

41 Поппер, К. Логика и рост научного знания / К. Поппер. – М.: Прогресс, 1983. – С. 159.

42 Патент № 2502999 Российская Федерация, Способ получения жизнеспособной гетерогенной популяции клеток кожи / С. В. Гольцов, Ю. Г. Суховей, П. П. Митрофанов; заявители и патентообладатели Гольцов С. В., Суховей Ю. Г.,Митрофанов П. П. – № 2012131976/15; заявл. 25.07.2012; опубл. 27.12.2013, Бюл. № 36.

43 Кларк, Р. А. Подавляющее большинство CLA+ Т-клеток находятся в нормальной коже / Р. А. Кларк, Б. Чонг, Н. Мирчандани и др. // Журнал иммунологии. – 2006. – Т. 176. – Вып. 7. – С. 4431–4439.

44 Терских, В. В. Стволовые клетки и структура эпидермиса / В. В. Терских, А. В. Васильев, Е. А. Воротеляк // Вестник дерматологии и венерологии. – 2005. – № 3. – С. 11–15.

45 Афанасьев, Ю. И. Кожа и ее производные / Ю. И. Афанасьев, Н. А. Юрина, Е. Ф. Котовский // Гистология, эмбриология, цитология / Под ред. Ю. И. Афанасьева, Н. А. Юриной. – М.: Медиа, 2012. – С. 553–581.

46 Караулов, А. В. Иммунология, микробиология и иммунопатология кожи / А. В. Караулов, С. А. Быков, А. С. Быков. – М.: Бином, 2012. – С. 122–125.

47 Патент № 2630607 Российская Федерация, Способ определения субпопуляционного состава клеток кожи и получения цитоиммунограммы кожи / С. В. Гольцов, Е. Г. Костоломова, Ю. Г. Суховей и др.; заявители и патентообладатели Гольцов С. В., Костоломова Е. Г., Суховей Ю. Г., Паульс В. Ю. – № 2016121997; заявл. 02.06.2016; опубл. 11.09.2017, Бюл. № 26.

48 Мелерзанов, А. Прецизионная медицина и молекулярная тераностика / А. Мелерзанов, А. Москалев, В. Жаров // Врач. – 2016. – № 12. – С. 25–26.

49 Теслинов, А. Г. Концептуальное мышление в разрешении сложных и запутанных проблем / А. Г. Теслинов. – СПб.: Издательство «Питер», 2009. – 288 с.

50 Иванов, А. Концептуальные технологии. Школа Спартака Никанорова / А. Иванов, А. Теслинов. – M.: НКГ «ДиБиЭй-Концепт», 2023. – 312 с. (Прикладные концептуальные исследования).

51 Бурбаки, Н. Структуры / Н. Бурбаки // Теория множеств. – М.: Мир,1965. – С. 242–297.

52 Никаноров, С. П. Концептуализация предметных областей / С. П. Никаноров. – М.: Концепт, 2009. – 268 с.

53 Иванов, А. Концептуальные технологии. Школа Спартака Никанорова / А. Иванов, А. Теслинов. – M.: НКГ «ДиБиЭй-Концепт», 2023. – 312 с. (Прикладные концептуальные исследования).

54 Концептуализация проведена под контролем команды концептуальных аналитиков А. Теслинова и А. Иванова.

55 Torvalds, L. Just for Fun / L. Torvalds, D. Diamond. – Harper Business, 2001. – P. 243–246.

56 Рузавин, Г. И. Методология научного познания: Учеб. пособие для вузов / Г. И. Рузавин. – М. : ЮНИТИ-ДАНА, 2012. – 287 с.

к предыдущей странице | читать далее | сразу к следующей главе