This chapter reflects on the role of the empirical approach in the clinical thinking of the dermatologist and emphasizes the inherent complexity of the human skin as an object of study, in light of its unique structural and functional characteristics. It argues that existing methods of skin examination do not resolve the problem of distinguishing cutaneous states at the cellular level, preventing modern dermatologists from fully assessing the functional activity of skin cell subpopulations in both health and disease. In doing so, the text reveals a fundamental contradiction that impedes the further theoretical and practical development of dermatology. It highlights the role of precision technologies—and specifically flow cytometry—as a means of overcoming this contradiction. Quantitative and functional analysis of skin cells is presented as a pathway toward a new understanding of the processes occurring in human skin at the level of cellular subpopulations.

“The truth shall set us free, but only if we recognize that there is more than one kind of truth.”

— Ken Wilber

Trends in scientific development clearly demonstrate how progress is linked to new research technologies and to advanced forms of scientific thinking. The latter is driven by a growing demand for accelerated emergence of individual breakthroughs and their rapid implementation, as well as for entire classes of discoveries capable of addressing pressing medical challenges.

In 2017, the Presidential Council for Strategic Development and Priority Projects of the Russian Federation defined the core performance criteria for the national healthcare system: accurate and rapid diagnostics, effective treatment, patient-centered care, accessibility, quality, and efficacy of pharmacological therapies. These priorities were formalized in Presidential Decree No. 254 of June 6, 2019, “On the Strategy for the Development of Healthcare in the Russian Federation for the Period Until 2025.” Notably, accurate diagnostics was designated as a primary goal.

At the same time, evolutionary adaptation is increasingly replaced by revolutionary breakthroughs driven by the synthesis of scientific knowledge—an outcome shaped by the current state of dermatology as a specialized field. Skin diseases remain highly prevalent: in 2016, they ranked among the top five disease groups in the Russian Federation. The incidence of skin and subcutaneous tissue diseases remained high among adults—approximately one in 25—and among children—one in 15. In absolute numbers, 8,604,183 cases of skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders were recorded, of which 6,240,955 were newly diagnosed.

Five years later, prevalence and incidence rates remained similarly high. Yet, despite the publication of the aforementioned Decree, neither breakthrough technologies nor integrative scientific solutions capable of revolutionizing the study of skin diseases have appeared in the accessible literature. This gap is evidently a consequence of the extraordinary complexity of studying human skin—an organ composed of a vast number of cells and an equally vast diversity of cellular relationships involved in the pathogenesis of numerous diseases.

Dermatology, with documented origins as far back as ancient Egyptian papyri dated to 1552 BCE—and even earlier references found in Sumerian texts three millennia prior—can rightly be considered one of the oldest medical sciences. Over centuries, it has accumulated extensive knowledge in the form of atlases, manuals, methodological guides, and treatment protocols. Researchers of both the Russian and international dermatological schools have contributed significantly to our understanding of the morphofunctional properties of human skin. With its remarkable diversity of cellular interactions, the skin functions as a system of reactions manifested as visible morphological elements, and clinical diagnosis of skin diseases continues to rely on standardized traditional approaches.

Yet, despite the undeniable value of this historical legacy, I allow myself to challenge a tradition that dates back to Hippocrates. In that tradition, dermatology has always been viewed as an empirical science grounded in the classification of observable external manifestations. This tradition of observation—shaped by practical experience—has historically evolved as a sequence of subjective assumptions followed by their refutation. Each new generation of dermatologists has been (and continues to be) given the opportunity to personally experience the full spectrum of diagnostic difficulties. By correlating previously acquired knowledge with their own observations, dermatologists reinforce the paradigm of empirical diagnostic behavior—without creating prerequisites for the further development of the field.

Karl Popper captured this phenomenon with clarity in his reflections on common sense:

“…From repeated observations made in the past, we believe that the sun will rise tomorrow because it has done so before. It is taken for granted that our belief in such regularities is justified by the very observations that gave rise to it.”

Why dermatology researchers continue to place unquestioning trust in empirical judgments remains a mystery.

It is obvious that anyone can visually assess the condition of the skin. A dermatologist’s assessment is more refined than that of a layperson, but it remains subjective and depends on the specialist’s experience, length of practice, and number of patients seen. Unlike everyday observations, which are largely incidental and unstructured, a dermatologist’s observations are purposeful. They cannot be passive acts of contemplation, because the physician’s mind not only reflects but also constructs the perceived reality—allowing for errors, misconceptions, and illusory interpretations that inevitably lead down a false diagnostic path. A human being can convince themselves of anything.

This is well illustrated by the diagnostic algorithm used in dermatology, which is essentially an empirical framework built from accumulated interactions with the phenomena and objects of dermatological practice—that is, the observable states of human skin.

Although skin diseases present with a great variety of symptoms, diagnosis often relies on one or several primary morphological elements. What is not taken into account is that the origin of each such element is determined by unique features not only of the skin as an organ but also of the individual patient. Symptom clusters are grouped into a diagnosis—or rather, multiple possible diagnoses. Having become twice removed from the biological substrate, the dermatologist then proposes a universal therapeutic strategy based on subjective impressions and empirical experience. Everything becomes “justified”: the familiar element validates the symptom; the recognizable symptom validates the diagnosis; and the diagnosis—through clinical guidelines—validates the prescribed treatment.

The dermatologist does not simply observe symptoms—they selectively choose those that support their presumptive hypothesis. These hypotheses, in turn, coalesce into diagnostic categories. To develop a mental image of each diagnosis requires experience and time, confirming that dermatology, in its present form, remains an empirical science.

A dermatologist treats what they see, and they see what they know.

Yet the fundamental hallmark of a science is not the transmission of experience, but the capacity to predict. David Hume wrote nearly three centuries ago that repetition offers no true evidential strength, despite its dominant role in human understanding. It is surprising that we have yet to absorb this lesson.

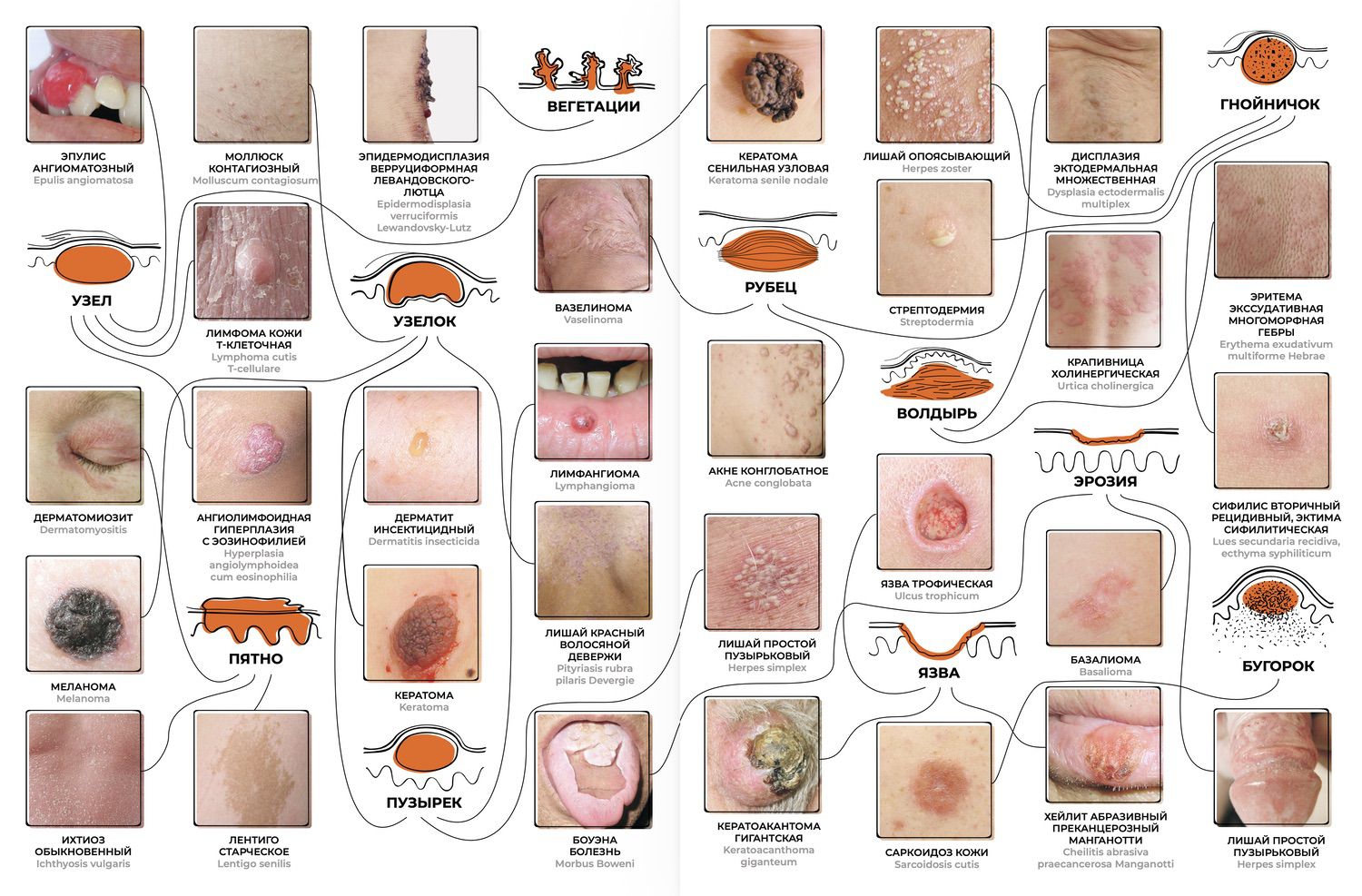

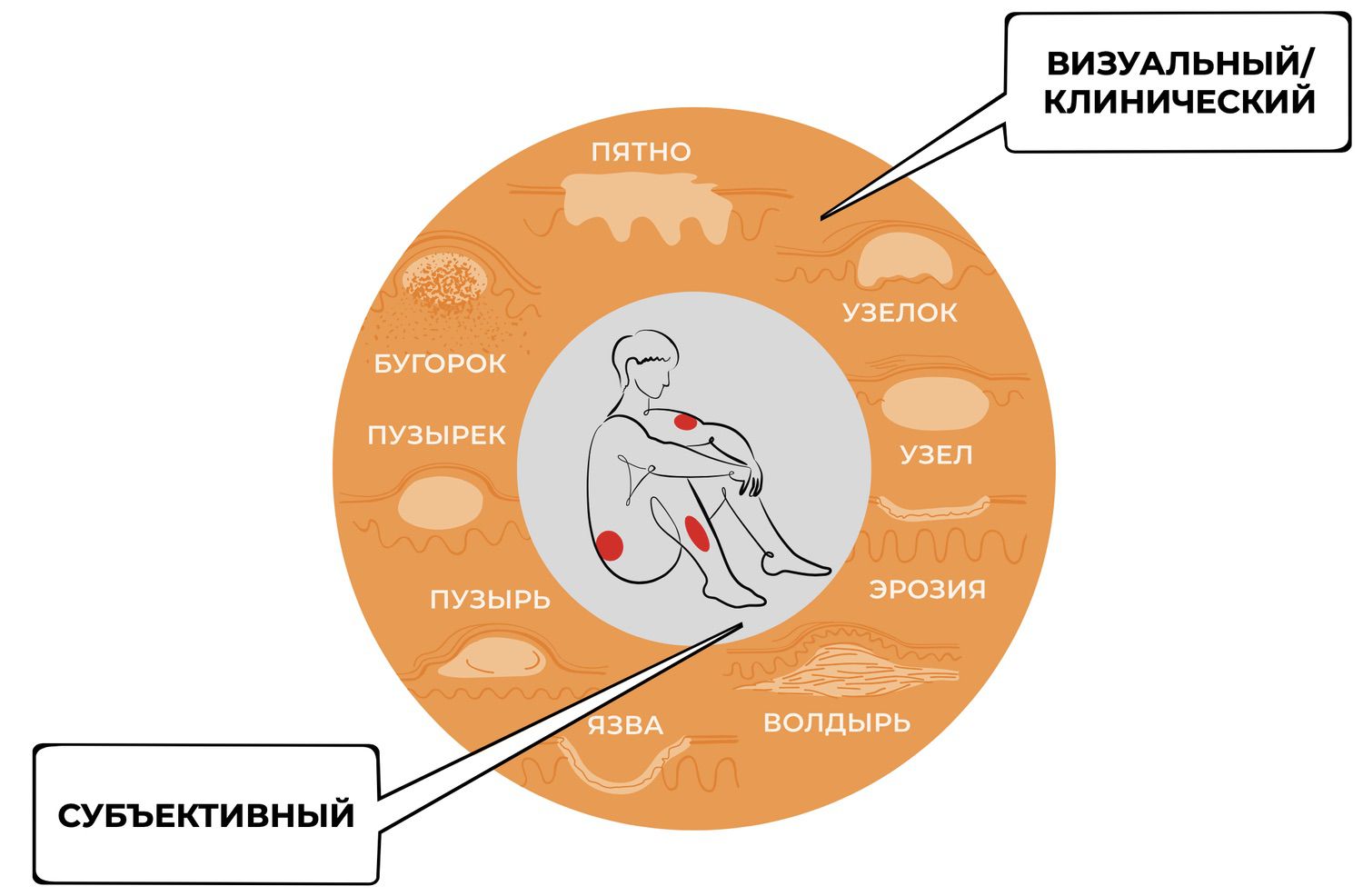

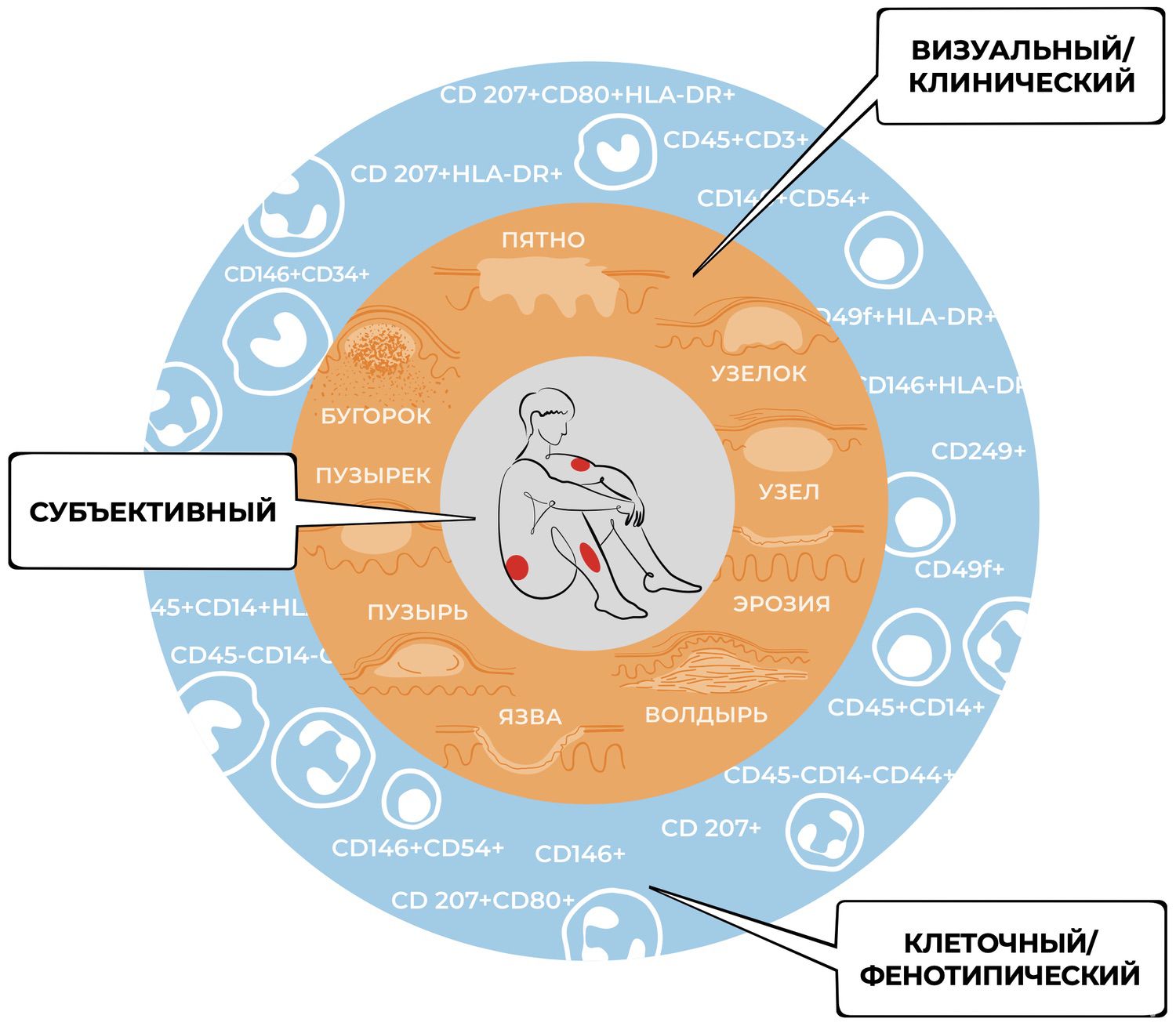

Today’s dermatologist recognizes roughly two dozen key signs—primary and secondary morphological elements of a rash. Their combinations and transformations form a diagnostic field expressed through numerous diseases (Fig. 1–15).

Fig. 1–15. A schematic representation of the dermatologist’s cognitive process in evaluating morphological elements of a rash and correlating them with known diseases.

Through this cognitive process, the dermatologist attempts to position themselves within that point in pathogenesis where the greatest concentration of familiar pathological changes has accumulated—where the “critical mass” of structural and functional disturbances becomes empirically recognizable. This leaves no opportunity to escape the vicious cycle of trial and error or to achieve predictive, effective strategies for diagnosis and treatment.

During a visual diagnostic test in which dermatologists were asked to propose a diagnosis based solely on clinical photographs, seven out of ten colleagues—with more than ten years of clinical experience—failed even to suspect dermatomyositis. And yet, what could be simpler? Edematous, wine-red erythema of the face, neck, dorsal hands, and knees may remain the only manifestations of this disease for a long time. In the presented case, a peri-orbital, goggle-shaped erythema—giving the face a “tearful” appearance—was combined with typical symmetrical lesions on the trunk and extremities (Fig. 16). Two dermatologists assumed generalized rubromycosis, and one suggested toxicoderma.

Figure 16. Clinical photographs of a patient with confirmed dermatomyositis used for testing dermatologists’ diagnostic reasoning.

Visually, one may propose these and many other diagnoses, each requiring further testing or manipulation of individual rash elements. These manipulations, intended to bring order to the diagnostic thinking of the dermatologist, often become keys that open the door to diagnostic uncertainty.

Morphological elements of the rash—expected to systematize the dermatologist’s reasoning—frequently become triggers that unlock new layers of diagnostic ambiguity.

By virtue of their simplicity as criteria for initial assessment, rash elements reinforce an already strong need among dermatologists to detect patterns that justify subsequent steps, including treatment decisions. This dependency often forces the observer to find patterns even where none exist and never existed (Fig. 17).

Figure 17. The paradox of the diagnostic loop.

The centuries-long use of a handheld magnifying lens for examining rash elements stemmed precisely from a physician’s desire to see more clearly and identify additional criteria of differentiation. A direct descendant of this approach is epiluminescence dermatoscopy, now indispensable in the diagnostic evaluation of skin neoplasms, where visual findings demand unequivocal interpretation.

That dermatology continues—even millennia later—to rely so heavily on visual diagnosis leads to an inevitable consequence: the persistent use of symptom-focused therapeutic strategies. Dermatology continues to pursue uniform treatment options designed to address a wide range of conditions in a broadly applicable manner.

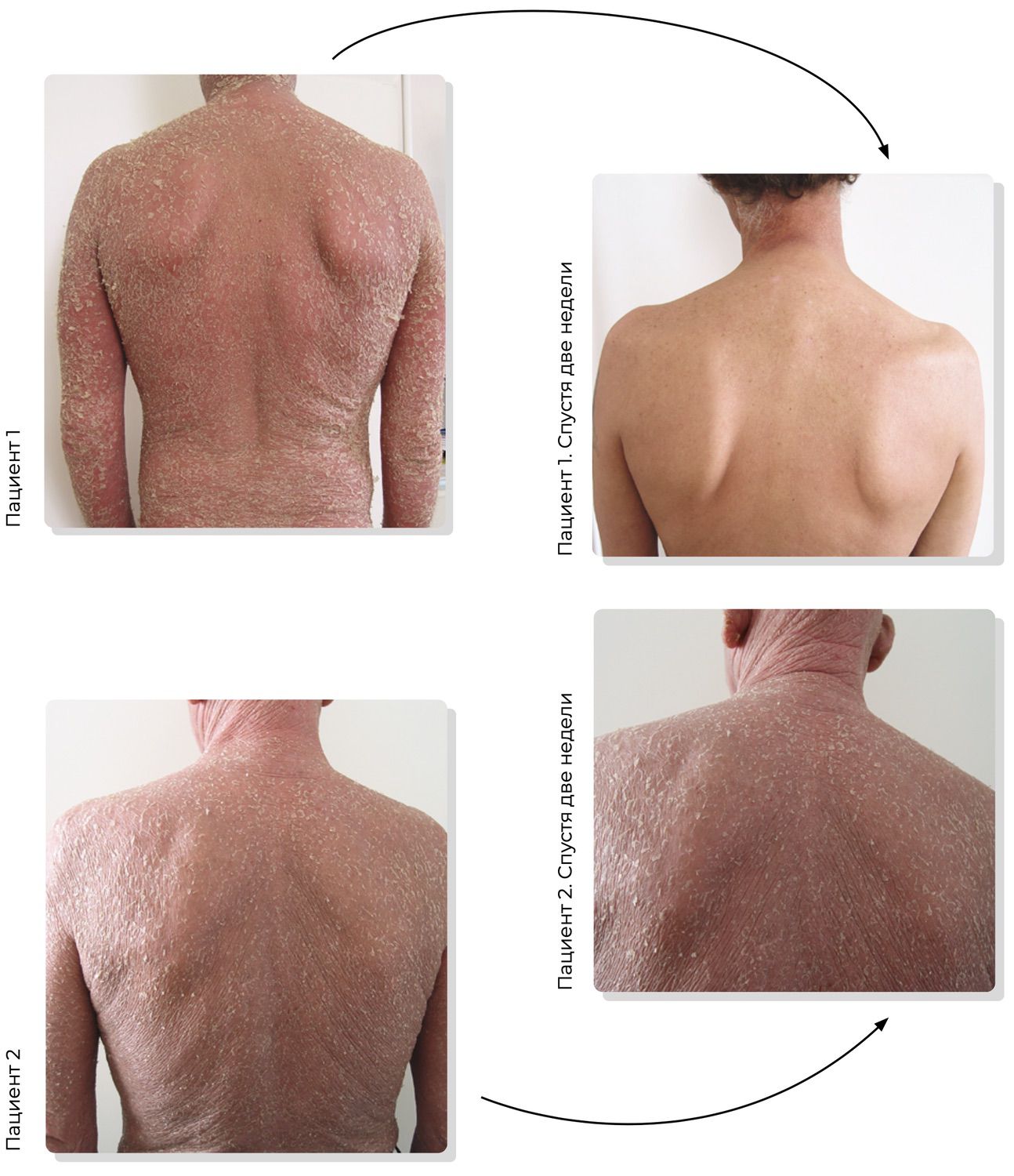

While such an approach may improve certain clinical metrics, it simultaneously demonstrates that the paradigm itself has reached the limits of its developmental potential. To illustrate this, consider two clinical cases (Fig. 18).

Figure 18. Two clinical cases. Patient 1 (51 years) and Patient 2 (54 years) presenting for initial dermatologic evaluation with complaints of trunk eruptions.

From the shoulder-scapular joint region, it is clear these are two different individuals. Visually and anamnestically, however, both patients exhibit strikingly similar clinical presentations. One might even argue that they appear indistinguishable. But is that truly the case? Do they share the same diagnosis?

Following the traditional diagnostic framework—one based on describing visible rash elements—we may generate a range of possible diagnoses: lymphoma, erythroderma, psoriasis, eczema, toxicoderma… and several others. Treatment guided by the 2015 Clinical Guidelines for Dermatovenereology led to dramatically different outcomes: Patient 1 demonstrated rapid improvement and was discharged after two weeks and returned to work, while Patient 2 died four months after diagnosis (Fig. 19).

Figure 19. Comparison of therapeutic effectiveness at the clinical-diagnosis stage.

This is far from the only instance in which the clinical diagnosis is refined to its final form far too late.

The lack of pathogenetic knowledge connecting morphological manifestations of skin diseases with their underlying mechanisms forces dermatologists to simplify what they observe into familiar diagnostic categories, grounding both diagnosis and treatment almost exclusively in visual assessment. In many cases, when establishing a diagnosis, the dermatologist relies on abstract concepts whose relationships only loosely approximate the real interactions among skin cells and their functions. Undoubtedly, diagnoses have value precisely because they reflect, albeit imperfectly, certain properties and relationships within the observed clinical constellation. This allows the clinician to describe what is seen and, through language, accumulate and transmit knowledge.

Yet, when discussing the visible portion of inflammatory processes and the pathogenetic mechanisms underlying them, these processes must be viewed as components of a single integrated whole—more precisely, as a system of heterogeneous elements unified into one entity: the human skin. Through functional interactions, these components generate the full spectrum of rash elements and their transformations observed in dermatological practice.

Both individual rash elements and the skin as a whole undergo qualitative changes driven by alterations at the level of cells and surface-active molecules that reflect cellular functions. For diagnostic judgments to be objective, these molecular and cellular events must be described quantitatively, because each skin cell should be regarded as a distinct entity composed not only of internal structures but also of membrane-associated molecular events that correspond to specific stages of differentiation, proliferation, activation, apoptosis, and other functional states.

As a two-component tissue system consisting of the epidermis and dermis, the skin includes numerous cell subpopulations, each assigned a specific functional role. Forming a large interface with the external environment and serving as a major barrier tissue that separates the internal milieu from external threats, the human skin has historically evolved into an autonomous organ of the immune system—one that frequently serves as the primary battleground for the activation of immune responses. With its diverse immune-competent cells cooperating through complementary surface structures and immunoregulatory cytokines, the skin functions as an active immune organ in which both resident and recirculating cells of the epidermis and dermis are capable of initiating inflammatory processes either systemically or in situ, combining the features of local functionality with integration into the organism-wide immune network.⁵

Simultaneously, the skin remains under continuous multilevel immune surveillance. On one hand, this system establishes a barrier enabling the elimination of foreign agents penetrating through the skin (microorganisms, proteins, allergens, haptens, etc.). On the other, it maintains tissue homeostasis by regulating cellular viability and the majority of functions executed at the level of specific subpopulations and molecules. As early as 1983, Dieter Streilein introduced the concept of skin-associated lymphoid tissue, referring to immune system components localized in the epidermis: antigen-presenting cells, T lymphocytes with epidermotropic properties, keratinocytes, and regional lymph nodes.⁶ This concept was later expanded to include the entire skin, where both innate immune factors and elements of adaptive immunity were subsequently identified.

Disruption of both local and systemic immune compartments underlies most skin diseases⁷, and skin-resident cells and cytokines play a direct role in these processes.⁸ This leads to a wide spectrum of immunopathological reactions and manifests as the enormous diversity of clinical presentations seen in dermatology.⁹ Such heterogeneity creates profound epistemic difficulty for the dermatologist during examination.

The high density of Langerhans cells, dermal dendritic cells, macrophages, subsets of T and B lymphocytes, plasma cells, and natural killer cells in the dermis¹⁰—combined with the dynamic physiological renewal of recirculating lymphocyte pools shuttling between regional lymph nodes, blood, and skin¹¹ to maintain immune homeostasis—renders the study of cellular subpopulation properties extraordinarily challenging. At the same time, this complexity reveals an opportunity to explore mechanisms that dermatologists, until now, have considered only theoretically.

At the same time, the development of medical science is accompanied by the emergence of new terms and approaches. For example, the term personalized medicine first appeared in 1998. Medicine of the future was initially described as the “three Ps”: predictive, preventive, and personalized. The term was later expanded into the concept of “five-P medicine,” integrating the original three with participatory and precision medicine.¹²

Nobel laureate Jean Dausset (1980), who introduced the term predictive, emphasized that the primary goal of medicine is to prevent disease. Predictive medicine (from Latin predictio — to foretell) encompasses all forms of forecasting the health trajectory of an individual patient or groups of patients. Yet, modern diagnostics has advanced technologically to such an extent that the once-humorous phrase “There are no healthy people—only under-examined ones” has become remarkably accurate. Nevertheless, the ability to anticipate and prevent disease leads to substantial savings in both material and human resources.¹³

The main objective of preventive medicine (from Latin praeventio — to prevent) is to avert the onset of a pathological condition or prevent its progression to the next stage.¹⁴ The highest degree of personalization—across predictive, preventive, and therapeutic interventions—became possible only with the rise of contemporary scientific progress, although the idea of personalized medicine itself has been considered significant long before then. As early as the 18th century, Matvei Mudrov introduced the practice of composing detailed medical histories, in which the current illness was viewed as the result of both environmental and hereditary influences.

The term precision medicine, which emerged with the advancement of biomedical and information technologies,¹⁵ united traditional medical approaches with modern genetic and molecular diagnostic methods. The term first appeared in Clayton Christensen and Jason Grossman’s book Innovator’s Prescription (2009), and was later used in the report Toward Precision Medicine by the Institute of Medicine of the U.S. National Academy of Sciences (2011). In 2015, a plan for a National Precision Medicine Initiative was proposed,¹⁶ prioritizing the study of biological samples obtained from research volunteers, enabling the analysis of a broad spectrum of diseases.¹⁷ ¹⁸ The discovery of DNA and elucidation of its functions laid the foundation for the development of technologies capable of providing detailed insights into the structure and function of all cellular molecules.¹⁹

Enhancing the system for early disease detection is one of the priority goals of state health policy in the Russian Federation. This is reflected in Presidential Decree No. 204 of May 7, 2018, “On National Goals and Strategic Development Tasks of the Russian Federation for the Period Until 2024,” which states that early detection of diseases—through the introduction of new diagnostic technologies—is a critical objective of modern diagnostics.²⁰

A long-overdue necessity has arisen for the development of diagnostic methods that fully align with the recommendations of the great Russian clinician Matvei Mudrov, who, two centuries ago, urged physicians to “treat the patient, not the disease.”

There are numerous widely accepted methods for the early diagnosis of skin diseases. In most cases, diagnostic evaluation begins with an invasive blood draw from the median cubital vein, followed by laboratory testing aimed at identifying deviations from normal blood parameters or the presence of specific disease-associated cells and biomarkers. Indeed, all organs, tissues, and individual cells of the human body leave traces of their biological status and functional state in the form of molecules entering the bloodstream.²¹ However, existing blood tests often cannot detect events occurring at the cellular level within an inflammatory infiltrate. As a result, in severe or refractory cases, clinicians may fail to recognize the specific features of the local skin condition in time—precisely as demonstrated in the earlier example.

Noninvasive methods of skin assessment—corneometry, sebumetry, cutometry, profilometry²²—and deeper imaging modalities such as optical coherence tomography, ultrasound microscopy, and magnetic resonance imaging²³ can describe a range of biophysical properties of the skin. Yet, they do not allow evaluation of the complex network of intercellular interactions. Despite their value in solving individual dermatologic tasks, these methods do not provide reliable quantitative information about functional differences among skin cells.

An exception is confocal laser scanning microscopy, which has become one of the most widely used fluorescence microscopy techniques for three-dimensional structural studies of cells and tissues. The flexibility of this method has enabled its use in a broad array of applications—from rapid visualization of dynamic processes in living cells to detailed morphological analysis of tissues. As a noninvasive diagnostic tool for skin diseases, its resolution approaches that of histopathological examination, with reported sensitivity and specificity ranging from 80% to 98.6%, and it may eventually replace traditional histology.²⁴ However, confocal images are grayscale and represent horizontal optical sections (in contrast to the vertical sections obtained by biopsy), which can complicate comparison with conventional histopathologic data.²⁵

Although these methods describe several skin properties, none can provide reliable information on the functional differences among skin cell subpopulations—cells constantly exposed to environmental influences and engaged in uninterrupted, complex intercellular interactions.

Advances in fields adjacent to dermatology—immunology and cytology—are driving technological renewal within dermatology itself, which increasingly requires in vivo morphofunctional diagnostic methods. The limitations of the methods listed above (in the context of dermatology and precision diagnostics) make it necessary to search for approaches that enable direct study of skin cells, especially given that the growth in the diversity of skin diseases far outpaces the adoption rate of new diagnostic technologies.

Considering the above, and acknowledging that skin function is governed by the specialization of its cellular subpopulations—and that visually recognizable patterns of skin disease merely reflect the end result of complex intercellular interactions—the direct study of skin cells becomes both timely and justified. Several points support this conclusion:

The unique structural connections between skin cells, which prevent their separation and study in a viable state in vitro, create a barrier to the advancement of dermatology—one that cannot be overcome without new technologies.

Within the existing dermatologic paradigm, which relies heavily on visual diagnostics and cautiously employs advanced investigative methods, no new conceptual challenges arise that could serve as catalysts for scientific development rather than mere refinement.

The current state of dermatology, marked by increasing disease diversity, growing comorbidities, and slow adoption of diagnostic innovations, reflects the field’s limitations as both a theory and a practice.

Potentially, this shift may reveal a wide range of clinical states that resemble known conditions but hold essential, yet unexplored, pathogenetic information at the level of skin cells. These states are numerous, and most have no names yet. This creates a natural impetus for dermatology to turn toward a cytological level of investigation.

For many skin diseases, the subjective-visual level of diagnosis has long required support from cellular and molecular insights.

Direct observation of membrane events occurring on the surface of skin cells is impossible; however, they can be inferred from the readings of a flow cytometer, and such values may legitimately be treated as observable phenomena.

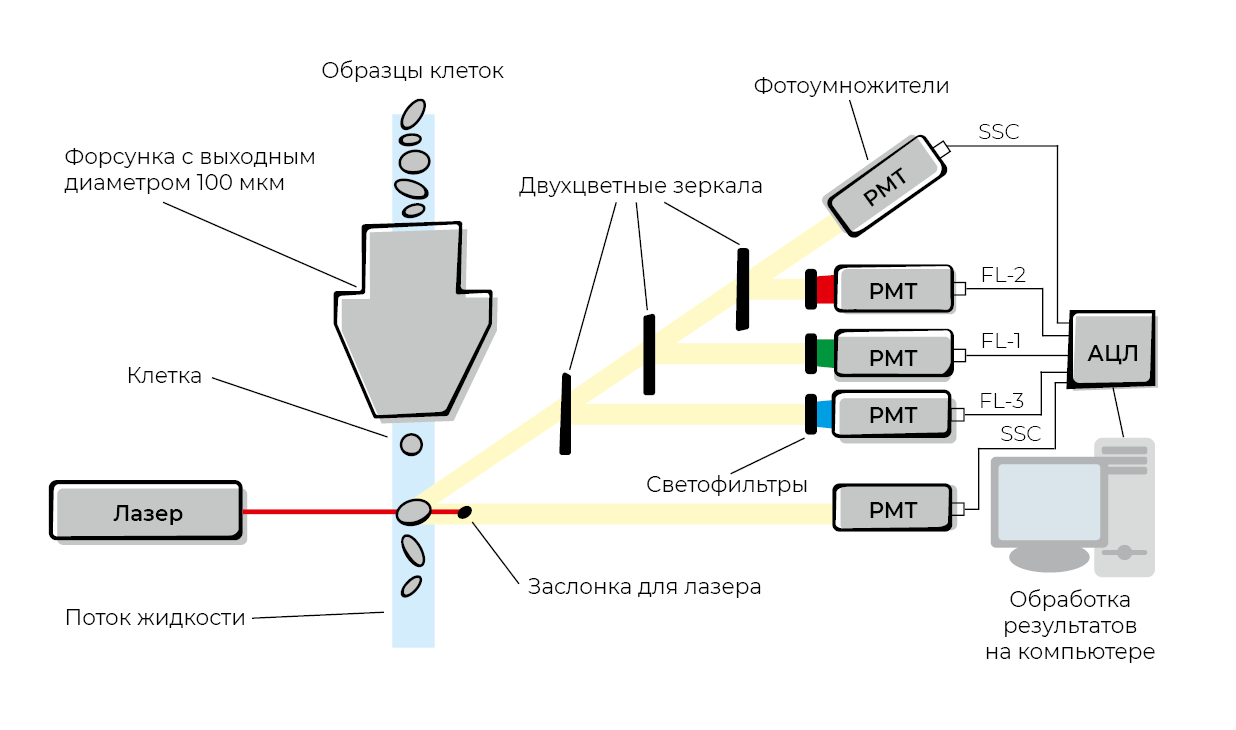

Flow cytometry is a method used to study dispersed media through single-cell analysis of elements in the dispersed phase, based on light-scattering signals and fluorescence from cell markers labeled with fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies directed against surface and intracellular components.²⁶

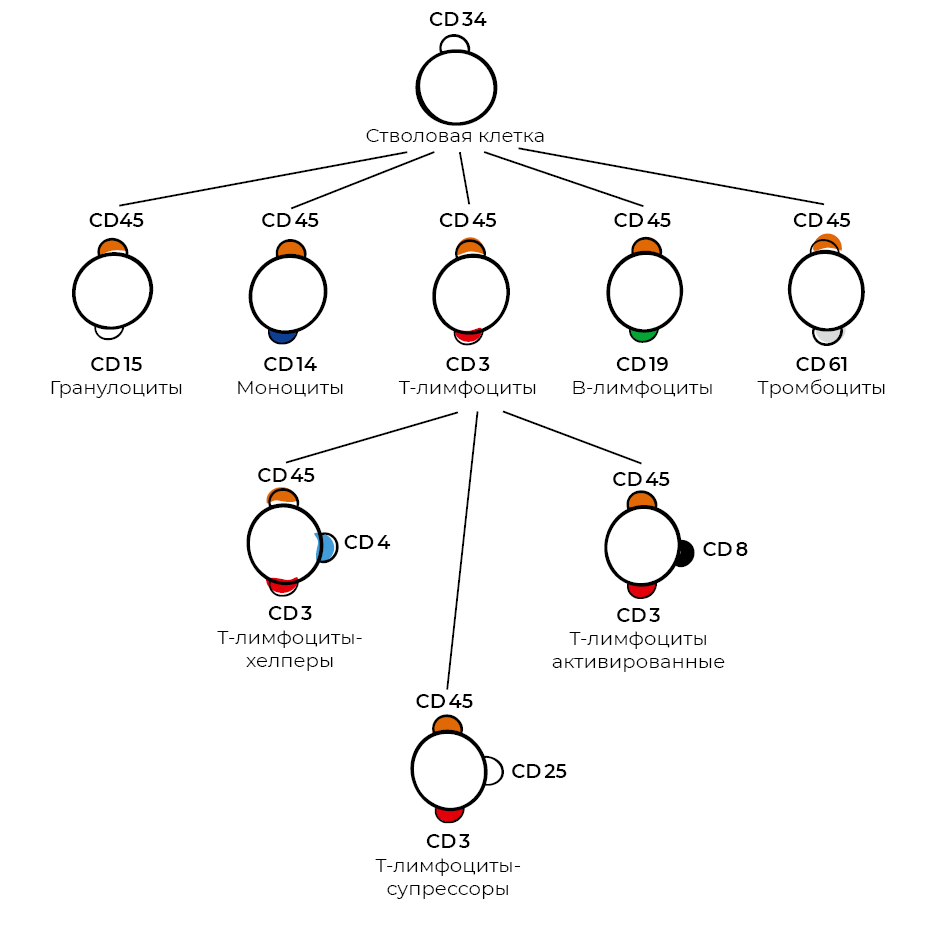

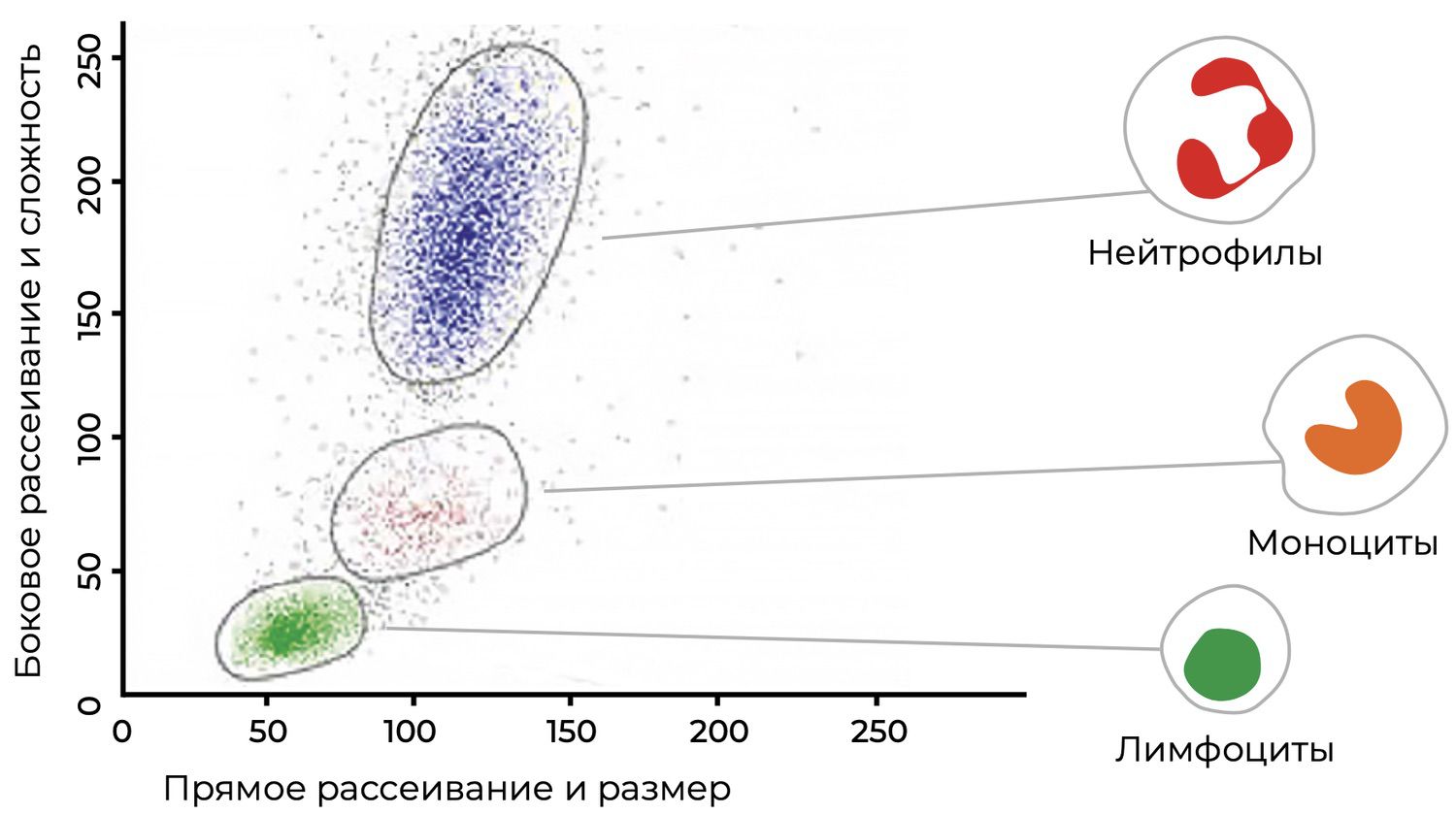

As a method for characterizing cells, flow cytometry emerged from the synthesis of histochemical and cytochemical analytical techniques. Further technological advancements provided researchers with an additional tool: monoclonal antibodies, which made it possible to classify cells not only according to their morphological attributes but also by their repertoire of surface antigens and receptors. Cell samples are stained with fluorescent monoclonal antibodies and then analyzed as a homogeneous cellular suspension using a laser. This enables detailed characterization of cells and allows the determination of their type and functional state according to the presence or absence of specific cellular markers—clusters of differentiation (CD). Identification and quantification of individual cellular subpopulations are performed through multiparametric analysis. Cell size and internal complexity (granularity) are determined by forward and side scatter, respectively, while fluorescence intensity indicates cell phenotype and viability (Fig. 20).

Figure 20. Schematic representation of the flow cytometry method.

Measurements obtained via flow cytometry offer insight into the morphological characteristics of cells (size, nucleus-to-cytoplasm ratio, cytoplasmic granularity, degree of asymmetry), allow the determination of subpopulation composition, and enable highly accurate assessment of functional states.²⁷

This technology provides a clear picture of cellular status and function and enhances our understanding of the mechanisms underlying cellular responses. Several key advantages make this method particularly valuable for research and diagnostic practice:

determination of absolute and relative numbers of cells within a sample;

phenotypic characterization of heterogeneous cell populations;

detection and analysis of rare cellular events occurring at frequencies of 10⁻⁵ to 10⁻⁷;

simultaneous measurement of multiple parameters for each individual cell;

high analytical throughput;

ability to characterize both surface and intracellular markers and to sort specific cell populations;

assessment of cell-cycle stages and proliferative activity;

simultaneous detection of multiple antigenic structures on a single cell.²⁸

However, the same authors note a limitation of flow cytometry: the complexity of preparing viable cell suspensions, especially when analyzing cells derived from solid tissues and organs.

It is worth recalling that the technique for generating monoclonal antibodies was invented in 1975 by Georges Köhler and César Milstein.²⁹ For this discovery, they received the 1984 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. The concept was to take a myeloma cell line incapable of synthesizing its own antibodies and fuse it with a normal antibody-producing B lymphocyte. Hybrid cells producing a specific antibody were then selected. This innovation quickly led to the development, by 1982, of the first cluster of differentiation classification—a standardized nomenclature of human antigens used to identify and study cell-surface proteins representing splice variants of extracellular domains. CD antigens (or CD markers) may be receptors or other proteins involved in cell–cell interactions and signal-transduction pathways (Fig. 21).

Figure 21. Scheme of blood lymphocyte differentiation according to function.

Monoclonal antibodies—based on the principle of specific antigen–antibody recognition—have become an integral tool for determining the phenotype of tissue-resident cells. They can be generated against virtually any protein (or protein fragment). The CD nomenclature is officially approved by the International Union of Immunological Societies and the World Health Organization; its continually expanding list now includes more than four hundred CD antigens and their subtypes.³⁰

The ability of monoclonal antibodies to recognize a single, specific epitope makes them highly sensitive reagents, enabling analysis of cell subpopulations, quantification of their proportions, and measurement of surface and intracellular markers. These parameters reflect the functional status of cells and can be visualized as distribution histograms (Fig. 22).

Figure 22. Histogram distribution of blood lymphocytes using monoclonal antibodies.

In this regard, flow cytometry is universally recommended for qualitative and quantitative evaluation of cell populations in patient samples and for certification of biological products.³¹ Why such a remarkable technology has not yet found practical application in dermatology remains an open question.

This is especially paradoxical given that a flow cytometer can enumerate individual cells and the membrane molecules they express within a population of millions, and classify them by size or functional state—activation, proliferation, or dynamic phenotypic changes—at a data acquisition rate of up to 1,000 events per second in real time, using only a single sample from a patient.

Flow cytometry is indispensable for identifying, characterizing, and isolating progenitor cells, as well as detecting changes within individual cells in heterogeneous populations. It is already widely used to study cell populations in bone marrow, lymphoid tissues, and peripheral blood.³² Because this method is inherently linked to mathematical analysis, standard antibody panels have been recommended to minimize errors in cytometric immunophenotyping.³³ This allows researchers to determine the roles of specific cellular subpopulations and their functions in disease pathogenesis, and to identify therapeutic perspectives.

Differences in immunophenotypes are already used in large-scale studies of cells isolated from various tissues:

umbilical cord blood: CD10, CD13, CD29 (integrin β1), CD49b (integrin α2), CD49c (integrin α4), CD49d (integrin α3), CD49e, CD51, CD73, CD90 (Thy-1), CD105, CD146, CD166 (ALCAM), CD14, CD31 (PECAM), CD33, CD34, CD45, CD38, CD56, CD123 (IL-3 receptor), CD133, CD235a;³⁴

endometrium: CD13, CD29, CD44, CD73, CD90, CD105, CD34, HLA-DR;³⁵

dental pulp: CD29, CD90, CD10, CD54, CD56, CD166, CD14, CD34, CD45;³⁶

bone marrow: CD13, CD44, CD73, CD90, CD105, CD31, CD34, CD45, CD117;³⁷

adipose tissue: CD29, CD44, CD73, CD90, CD105, CD166, CD14, CD31, CD34, CD45;

mesenchymal progenitor cell lines from bone marrow: CD29, CD44, CD73, CD90, CD105, CD166, CD14, CD34, CD19, CD45.³⁸

It is becoming increasingly clear that meaningful progress in dermatology is impossible without cell-based technologies. Such technologies have the potential to drive the renewal of dermatology, enabling detailed study of the processes underlying skin-cell diversity, specialization, and functional selectivity—and thereby expanding the dermatologist’s cognitive capabilities. In the present context, this means transitioning to a new level of symptom interpretation: the cellular, phenotypic level (Fig. 23).

Figure 23. Levels of cognitive activity in dermatology.

Meanwhile, dermatologists are increasingly witnessing the devaluation of terminology. A term borrowed from the literature and applied to diagnostic practice—practice that has significantly changed since the moment the term was originally defined—no longer explains what is observed. At best, this leads to disappointment in the descriptive power of the term; at worst, it directs the dermatologist down a path of misinterpretation.

The transition from empirical concepts to abstract theoretical ones represents a dialectical leap from the sensory-empirical stage of investigation to the rational-theoretical.

Because the relative and absolute numbers of cells expressing specific phenotypes constitute the final output of immunophenotyping—and because flow cytometry is the primary method of immunophenotyping³⁹—modern dermatology may soon be able to identify cell types and determine their functional states according to their marker profiles. This would enrich the diagnostic and therapeutic toolkit with forms of knowledge the field has never possessed before.

[1] Указ Президента РФ от 06.06.2019 № 254 «О Стратегии развития здравоохранения в Российской Федерации на период до 2025 г.» [Электронный ресурс]. – Режим доступа: http://kremlin.ru/events/councils/by-council/1029/54079.

[2] Кубанова, А. А. Анализ состояния заболеваемости болезнями кожи и подкожной клетчатки в Российской Федерации за период 2003–2016 гг. / А. А. Кубанова, А. А. Кубанов, Л. Е. Мелехина и др. // Вестник дерматологии и венерологии. – 2017. – № 6. – С. 22–33.

[3] Кубанов, А. А. Итоги деятельности медицинских организаций, оказывающих медицинскую помощь по профилю дерматовенерология, в 2020 г.: работа в условиях пандемии / А. А. Кубанов, Е. В. Богданова // Вестник дерматологии и венерологии. – 2021. – Т. 97. – № 4. – C. 8–32.

[4] Поппер, К. Объективное знание. Эволюционный подход / К.-Р. Поппер; пер. с англ. Д. Г. Лахути; отв. ред. В. Н. Садовский. – М.: Эдиториал УРСС, 2002. – С. 38.

[5] Боровик, Т. Э. Кожа как орган иммунной системы / Т. Э. Боровик, С. Г. Макарова, С. Н. Дарчия и др. // Педиатрия. – 2010. – Т. 89. – № 2. – С. 132–136.

[6] Streilein, J. W. Skin-associated lymphoid tissues (SALT): origins and functions / J. W. Streilein // J. Invest. Dermatol. – 1983. – V. 80. – P. 12–16.

[7] Bos, J. Skin immune system: Cutaneous immunology and clinical immunodermatology / J. Bos. – 2nd ed. – CRC Press, 2004. – 412 р.

[8] Bouwstra, J. A. Structure of the skin barrier, in Skin Barrier / J. A. Bouwstra, K. Pilgrim, M. Ponec; edited by P. M. Elias, K. R. Feingold. – New York: Taylor and Francis, 2006. – 65 p.

[9] Баринов, Э. Ф. Функциональная морфология кожи: от основ гистологии к проблемам дерматологии / Э. Ф. Баринов, Р. Ф. Айзятулов, М. Э. Баринова и др. // Клиническая дерматология и венерология. – 2012. – Т. 10. – № 1. – С. 90–93.

[10] Кузьмин, Ю. А. Кожа и иммунная система (обзор литературы) / Ю. А. Кузьмин, Ж. Б. Испаева, Г. Н. Маемгенова и др. // Vestnik KazNMU. – 2019. – № 2. – С. 296–300.

[11] Белова, О. В. Иммунологическая функция кожи и нейроиммунокожная система / О. В. Белова, В. Я. Арион // Аллергология и иммунология. – 2006. – Т. 7. – № 4. – С. 492–497.

[12] Щербо, С. Н. Лабораторная диагностика как основа медицины 5п / С. Н. Щербо, Д. С. Щербо // Вестник РГМУ. – 2019. – № 1. – С. 12–14.

[13] Hayes, D. F. Personalized medicine: risk prediction, targeted therapies and mobile health technology / D. F. Hayes, H. S. Markus, R. D. Leslie, E. J. Topo // BMC Med. – 2014. – Vol. 12. – P. 37.

[14] Сучков, С. В. Персонализированная медицина как обновляемая модель национальной системы здравоохранения. Ч. 1. Стратегические аспекты инфраструктуры / С. В. Сучков, Х. Абэ, Е. Н. Антонова, П. Барах и др. // Российский вестник перинатологии и педиатрии. – 2017. – № 3 (62). – С. 7–14.

[15] Щербо, С. Н. Персонализированная медицина: Монография в 7 томах / С. Н. Щербо, Д. С. Щербо. – Т. 1. Биологические основы. – М.: РУДН, 2016. – 224 с.; Т. 2. Лабораторные технологии. – М.: РУДН, 2017. – 437 с.

[16] Juengist, E. From «Personalized» to «Precision» Medicine: The Ethical and Social Implications of Rhetorical Reform in Genomic Medicine / E. Juengist, M. L. McGowan, J. R. Fishman et al. // Hastings Center Report. – 2016. – Vol. 46 (5). – P. 21–33.

[17] Collins, F. S. New Initiative on Precision Medicine / F. S. Collins, H. A. Varmus // The New England Journal of Medicine. – 2015. – Vol. 372. – P. 793–795.

[18] Nabipour, I. Precision medicine, an approach for development of the future medicine technologies / I. Nabipour, M. Assadi // International Journal of Information Management. – 2016. – Vol. 19. – P. 167–184.

[19] Eaton, L. Human genome project completed / L. Eaton // British Medical Journal. – 2003. – Vol. 326. –№ 7394. – P. 838.

[20] Указ Президента Российской Федерации от 07.05.2018 № 204 «O национальных целях и стратегических задачах развития Российской Федерации на период до 2024 г.» [Электронный ресурс]. – Режим доступа: http://www.kremlin.ru/acts/bank/43027.

[21] Zharov, V. Revolutionising blood testing / V. Zharov // Intern. Innovatn EU. – 2010. – P. 97–99.

[22] Агафонова, С. Г. Неинвазивные методы диагностики в дерматологии и дерматокосметологии / С. Г. Агафонова, Н. И. Индилова, Е. В. Иванова и др. // Экспериментальная и клиническая дерматокосметология. – 2010. – № 4. – С. 41–45.

[23] Золотенкова, Г. В. Современные неинвазивные методы оценки возрастных изменений кожи / Г. В. Золотенкова, С. Б. Ткаченко, Ю. И. Пиголкин // Судебно-медицинская экспертиза. – 2015. – № 58 (1). – С. 26–30.

[24] Кунгуров, Н. В. Конфокальная лазерная сканирующая микроскопия: опыт работы в ГБУ СО «Уральский научно-исследовательский институт дерматовенерологии и иммунопатологии» / Н. В. Кунгуров, Н. В. Зильберберг, М. М. Кохан, Е. П. Топычканова, И. А. Куклин, Е. В. Никитина, Е. В. Бакуров // Клиническая дерматология и венерология. – 2022. – № 21 (1). – C. 106–113.

[25] Потекаев, Н. Н. Конфокальная лазерная сканирующая микроскопия на примере Vivascope 1500: принцип работы и возможности применения в дерматологии / Н. Н. Потекаев, С. Б. Ткаченко, А. Ю. Овчинникова, Н. Н. Лукашева // Российский медицинский форум: Научный альманах. – 2008. – № 1. – C. 36–41.

[26] Vembadi, A. Cell Cytometry: Review and Perspective on Biotechnological Advances / A. Vembadi, A. Menachery, M. A. Qasaimeh // Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology. – 2019. – Т. 7. – Р. 147.

[27] Хайдуков, С. В. Подходы к стандартизации метода проточной цитометрии для иммунофенотипирования. Настройка цитометров и подготовка протоколов для анализа / С. В. Хайдуков // Медицинская иммунология. – 2007. – Т. 9. – № 6. – С. 569–574.

[28] Трусов, Г. А. Применение проточной цитометрии для оценки качества биомедицинских клеточных продуктов / Г. А. Трусов, А. А. Чапленко, И. С. Семенова и др. // БИОпрепараты. Профилактика, диагностика, лечение. – 2018. – № 18 (1). – С. 16–24.

[29] Kohler, G. Continuous cultures of fused cells secreting antibody of predefined specificity / G. Kohler, C. Milstein // Nature. – 1975. – Т. 256. – Р. 495–497.

[30] Posner, J. Monoclonal Antibodies: Past, Present and Future / J. Posner, P. Barrington, T. Brier // Handbook of experimental pharmacology. – 2019. – Т. 260. – Р. 81–141.

[31]European Pharmacopoeia: EDQM. – 8th ed. [Электронный ресурс]. – Режим доступа: http://online.edqm.eu/entry.htm.

[32] Donnenberg, V. S. Cytometry in Stem Cell Research and Therapy / V. S. Donnenberg, H. Ulrich, A. Tarnok // Cytometry, Part A. – 2013. – Т. 83 (1). – Р. 1–4.

[33] O'Neill, K. Flow Cytometry Bioinformatics / K. O'Neill, N. Aghaeepour, J. Spidlen et al. // PLoS Computational Biology. – 2013. – Т. 9 (12). – e1003365.

[34] Moretti, P. Mesenchymal Stromal Cells Derived from Human Umbilical Cord Tissues: Primitive Cells with Potential for Clinical and Tissue Engineering Applications / P. Moretti, T. Hatlapatka, D. Marten et al. // Advances in Biochemical Engineering/Biotechnology. – 2010. – Т. 123. – Р. 29–54.

[35] Домнина, А. П. Мезенхимальные стволовые клетки эндометрия человека при длительном культивировании не подвергаются спонтанной трансформации / А. П. Домнина, И. И. Фридлянская, В. И. Земелько и др. // Цитология. – 2013. – № 55 (1). – С. 69–74.

[36] Шаманская, Т. В. Культивирование мезенхимальных стволовых клеток ex vivo в различных питательных средах (обзор литературы и собственный опыт) / Т. В. Шаманская, Е. Ю. Осипова, Б. Б. Пурбуева и др. // Онкогематология. – 2010. – № 3. – С. 65–71.

[37] Boxall, S. A. Markers for Characterization of Bone Marrow Multipotential Stromal Cells / S. A. Boxall, E. Jones. – Stem Cells International, 2012 [Электронный ресурс]. – Режим доступа: https://www.hindawi.com/ journals/sci/2012/975871/cta.

[38]Американская коллекция типовых культур (ATCC) [Электронный ресурс]. – Режим доступа: http://www.lgcstandards-atcc.org.

[39] Vembadi, A. Cell Cytometry: Review and Perspective on Biotechnological Advances / A. Vembadi, A. Menachery, M. A. Qasaimeh // Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology. – 2019. – Т. 7. – Р. 147.

к предыдущей странице | читать далее | сразу к следующей главе